LATEST INSIGHTS

Your Present Location: LATEST INSIGHTSRadhika Desai: De-dollarization is about more than currencies: As dollar system declines, what comes next?

Source: Geopolitical Economy Hour Published: 2023-04-29

Transcript

(What follows is an edited transcript.)

RADHIKA DESAI: Hi everyone, welcome to this eighth Geopolitical Economy Hour, the fortnightly show on the political and geopolitical economy of our times. I’m Radhika Desai.

MICHAEL HUDSON: And I’m Michael Hudson.

RADHIKA DESAI: And this will be the fourth and final show on de-dollarization. As you know, we initially decided to do a couple of shows on de-dollarization, but Michael and I have written lots about it, both jointly and individually. And we have lots to say.

So it eventually became three programs, and even then it wasn’t over. So today we are into the fourth and final program. And as you know, we’ve divided our discussion into several questions:

What is money? Why does it appear to take national forms? Can there be world money?

What is the relation of money and debt?

Is money a commodity?

What is the ‘theory’ of how the dollar served as the world’s money?

Was it like the Sterling System? What was the sterling system?

How did the Sterling system end?

What really happened between the World Wars?

The dollar system between 45 and 71, when the dollar-gold link was broken. How did it work?

Was there really a ‘Bretton Woods II after 1971?

The crisis today? What are its main dimensions?

So there are the 10 questions, and we’ve dealt with the first nine. And today we’ll be dealing with the final question, which is: What are the dimensions of the crisis of the dollar system today?

And of course, as the Chinese saying goes, every crisis is an opportunity. So Michael and I also want to talk very much about: What are the opportunities contained in this current crisis for a policy paradigm, which is much kinder and better for development and for the prosperity of ordinary people around the world than has been possible over the last several decades of dollar dominance?

So that’s what we are going to talk about, isn’t it, Michael?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Yes, we’re going to talk about how really, it’s not simply moving out of the dollar, it’s de-neoliberalization. It’s really a whole creation of a whole different economic system that is necessary.

RADHIKA DESAI: Some people often talk about the contrast between the so-called Washington Consensus and the so-called Beijing Consensus and much of what we say will have to do with that.

So I think of what drives de-dollarization as being at least composed of two very different parts:

What drives de-dollarization?

WITHIN U.S.: CONTRADICTIONS MOUNT

-

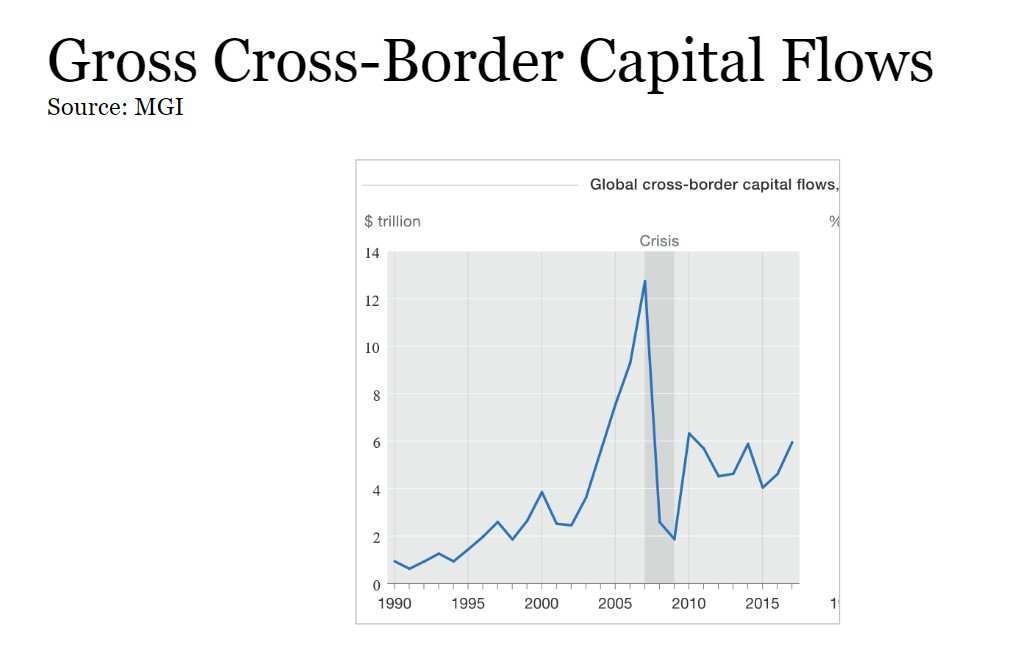

Capital inflows never recovered from 2007 peak

Federal Reserve has to support asset markets

Inflation is eroding the dollar

But Federal Reserve cannot rescue it without collapsing asset markets, which have been critical support for dollar

US assets, treasuries and others, less attractive

Weaponization of dollar financial system

OUTSIDE U.S.: ALTERNATIVES BEING CREATED

-

Bilateral arrangements for trade in national currencies and swap lines

Multilateral arrangements to provide finance and monetary support: CMI, SCO, NDB, CRA

New payments systems

CBDCs

Internationalization of other currencies

Increasing invocation of Keynes’ International Clearing Union (ICU) and Bancor ideas

Widening pluripolarity and weakening of imperialism: effects on commodity prices

So one is, one set of developments is occurring within the dollar system, the US financial system, which really forms the base upon which, then, the dollar tries to mount its contradictory, volatile and never-entirely-successful role as the world’s money.

So we look at how the contradictions are mounting there.

And then we will see that as the contradictions are mounting within the dollar system, outside there are a whole stream of possibilities and alternatives that are being created, centered, of course, around China, but also entailing the activities and policies and the new policies of other countries.

And of course, as you know, all these developments have been rapidly accelerated by the current conflict in which so many contradictions have been really maturing.

So if we look at the left hand side, the mounting contradictions of the dollar, we see that first of all, as we’ve talked about many times throughout this past several shows on de-dollarization, the dollar system after 1971 essentially rested on creating, on expanding, financial activity, dollar denominated financial activity in such a way that the rest of the world, holders of money of the rest of the world, would hold that money in dollars in order to take advantage of the opportunities for financial profit being created by the dollar system.

And what’s really interesting is that this inflow of dollars that has been central to keeping up the value of the dollar, to counteracting the downward pressure on the dollar that the US deficits and the declining US economy would create, this inflow has actually gone down considerably.

You will see in the graph that inflows grow faster, and as you can see, the inflow of dollars, the growth of dollars, the growth of the gross cross-border capital flows, the bulk of which are in dollars, you see them going up sort of in a series of peaks up to the really big peak of 2007.

And as you can see, that was like the mother of all asset bubbles. And after that, you see that the cross-border capital flows fall, and then they recover. But as you also see, the recovery has remained essentially at levels that are less than half of the 2007 peak. So that’s the real point.

So these inflows are declining. Michael, did you want to add anything?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Yes, the important thing is that what we’re talking about here, and what actually determines the relative exchange rates of currencies, is not trade.

In the newspapers, they talk about using the dollar for oil and for food and for other basic needs, but the actual change that is responsible for the up and down zigzagging are capital flows, mainly into the stock market and into the bond market.

And this is very largely a function of interest rates. And the exchange rates are really a function of financial markets, not trade particularly, especially foreign debt service.

Why do Global South countries need dollars to pay their dollar denominated debts? And this is what the papers leave out.

And once you begin to look at these factors, the capital flows that Radhika just mentioned and that we’re charting right now, you realize that if you’re having a system that’s not based on investment in each other’s private capital markets, but on a mixed economy with governments, we’re not talking about a market economy anymore.

Suppose we’re 10 years from now and we’re looking back at the chart that Radhika had just put up. Well, right now it looks up and down, but in 10 years, all this will be just a little squiggle and then there’ll be just a completely different world.

RADHIKA DESAI: Well, exactly. And you know, Michael, you raise a really interesting point.

But before we get to that, let me also add one other thing.

What Michael says is that, this entire dollar system is organized not around production, not around trade, which is basically what ordinary people need in order to make their living. But it is essentially organized around finance.

That is to say, in the indebting of ordinary individuals, businesses, productive businesses and governments. And it is centered around creating speculative asset markets.

Not only does this not feed anybody apart from making a few people very rich by transferring income from some people to others, but it also strangulates production.

And in addition to that, by creating such a demand for the dollar, which essentially is a demand that mainly rich people and big institutions engage in that they supply, what this system has also done is it has brought the exchange value of most currencies other than the dollar down.

That is to say, the dollar is overvalued in relation to all these other currencies, which means ordinary people in poor countries not only have to work hard in order to earn dollars, they have to work unreasonably hard because the dollar is unreasonably overvalued.

And of course, as Michael says, this is what they need to do in order to pay the debt, which is also the other net on which this resides, because governments of the Third World and increasingly also businesses of the Third World are indebted to the dollar system.

So now, Michael also mentioned one other thing, which is that for this so-called market system, we are always told that the market is operating freely and the dollar’s value is the value determined by the free market. But actually, there’s something really fishy going on.

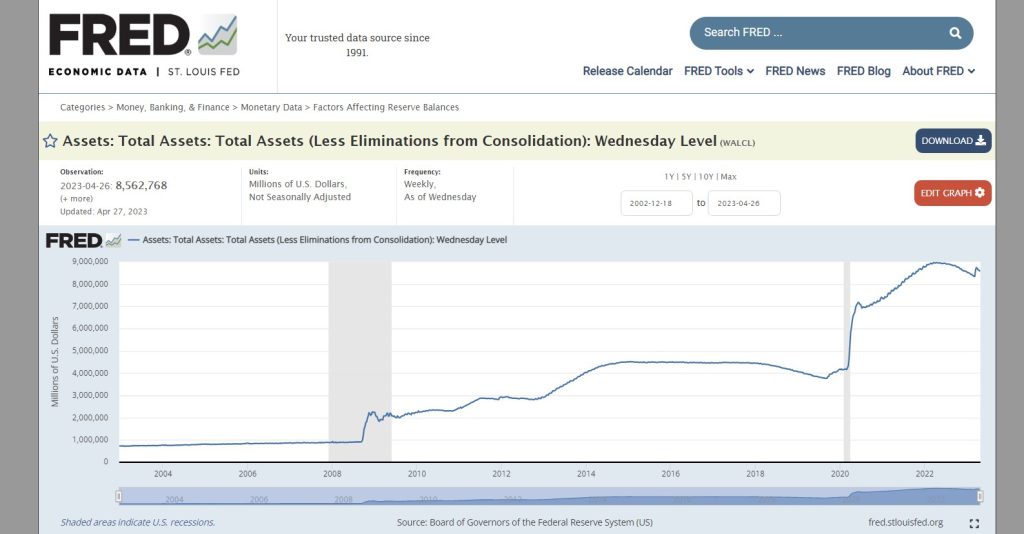

So if you see here, basically what we are also arguing is that the Federal Reserve has had to step in in a big way and support asset markets.

So here you see simply a graph of the dollars, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. And you can see that from being at about a trillion dollars before 2008, it sort of jumped to twice the amount soon thereafter. And then in the process of quantitative easing, it went up to about four trillion dollars.

And then in the last two or three years, given the pandemic crisis and the need to hold up asset markets, you can see it doubled again in size. So today, the value of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet is over nine trillion dollars.

Why are we showing you this? This is the amount of money, which in addition to all the other shenanigans, including low interest rates, et cetera, that the Federal Reserve is using in order to prop up asset markets.

Why does the Federal Reserve need to prop up asset markets? Because foreign money is no longer coming in to the same extent that it would need to in order to keep asset markets up.

And if these asset prices were to fall, which they would without the intervention of the Federal Reserve, then of course the wealth of the richest US and world elites would be wiped out. And the Federal Reserve is indebted to nobody other than these elites.

So that’s the next thing we wanted to show you.

MICHAEL HUDSON: One thing about this, the Federal Reserve, by doing the quantitative easing, has painted itself into a corner.

And the corner is what you saw a few weeks ago with Silicon Valley Bank and now the other San Francisco banks that are going under.

If interest rates were to rise, then the banks would become insolvent because the value of stocks or bonds is discounted by the exchange rate. I know that may sound technical for some people, but when interest rates rise, it’s basically a repayment period.

And so the Federal Reserve has a problem. And it seems to have just discovered this now, that if you have a zero interest rate, then people are going to buy stocks and bonds.

And one of the reasons that the dollar has remained strong is that the American stock market has gone up so fast and compared to other markets, including Japan and Europe, that foreign investors, the billionaires all over the world, are putting their money into riding the stock market rise.

But if the Federal Reserve now decides, wages are beginning to go up and we’ve got to create unemployment and bring on a depression so that we can lower the wages and make even bigger profits, then you’re going to have the banking system here and in Europe going insolvent. And that’s what you’re seeing right now.

So the system has reached an insolvable crisis. It’s not a problem. It’s a quandary. There’s nothing the Federal Reserve can do. And the whole dollarized system is breaking right now in the United States. It’s paralyzed.

It can’t raise the interest rates without making all the banks look like Silicon Valley Bank, insolvent and on the balance sheet where the assets lower their value below the deposit liabilities.

Banks owe depositors money. The banking for these deposits are the banks’ holding of stocks and bonds. If interest rates go up and stock and bond prices and real estate prices go down, then the banks no longer can cover their reserves.

The nine trillion dollars that Radhika just mentioned is the insolvency of the bank. Within one month, the government would have to create another nine trillion dollars to give to the banks to cover the deposits. And that’s crazy.

RADHIKA DESAI: Well, absolutely. In fact, you know, it’s both. It’s this vast inflation of the US Federal Reserve’s balance sheet that, as Michael says, represents the insolvency of banks.

But I would add one other thing. It represents the illiquidity of asset markets.

That is to say, you know, an asset market is only liquid if whenever you want to sell your holding of that asset, there is a buyer for it. And that is no longer so, which is why the Federal Reserve has stepped in to act as the buyer of last resort for these asset markets.

And the quandary that Michael talks about, this is absolutely key. And we have talked about this actually for several years, including in our 2020 paper “Beyond the Dollar Creditocracy” and even going back before it.

And this has also been my argument, actually going back even more years. Essentially throughout the 21st century, and certainly since 2008, the Federal Reserve, in order to prop up a declining financial system and an increasingly volatile and vulnerable financial system, has been pursuing a zero, or very low, interest rate policy.

And this has not only supported the banking structure, which was already vulnerable, but by supporting it in this way, the Federal Reserve papered over the vulnerabilities of this banking system. And of course, it also inflated the value of financial assets.

And now the resurgence of inflation, which the Federal Reserve cannot combat or will not combat, I should say, through any other means but by raising interest rates, the Federal Reserve is caught between a rock and a hard place.

If they raise interest rates, the whole financial house of cards comes crashing down. And if they don’t raise interest rates, inflation will bring down the dollar and also have an effect and act as a drag on the economy, on the financial system, et cetera.

So in this way, essentially, the return of inflation is a crisis of the dollar system itself. And I would also add that it is a crisis of the imperial system in the simple sense that one of the key foundations of imperialism is to keep the resources that come to rich countries, particularly the United States, cheap.

And as the dollar goes down in value, as inflation goes up, these things are no longer cheap and they can no longer essentially keep the cost of living down and the cost of production down in these countries.

The next contradiction is that in fact, the inflation of course is eroding the dollar. And we’ve also talked about how the Federal Reserve cannot reverse it without collapsing asset markets. So we’ve done that.

But the next problem is that US assets, including US treasuries, are becoming less attractive.

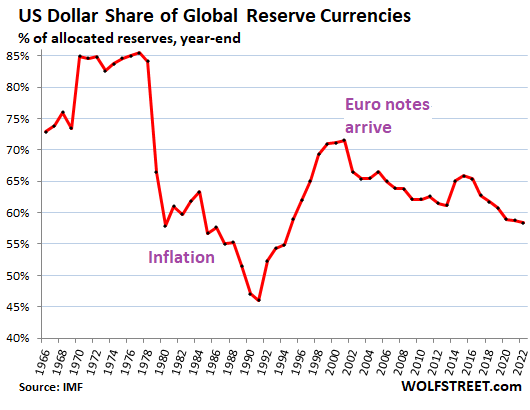

So if we go to the next graph, what’s very clear is that the US share of global reserve currencies has declined quite substantially. So you see here right up to the end of the 1970s, it is very high, at about 85% of the dollar’s share of global reserves.

Then it falls as a result of the crisis of the late 1970s, which Paul Volcker had to react to by massively raising interest rates. And this saved the situation, but the dollar’s share of global reserves kept falling.

And then in the 1990s, it went up. And that’s also a really interesting story. It went up because of a series of financial crises that afflicted other countries, largely thanks to their participation in this volatile dollar system.

And in reaction to this, in order to keep capital accounts open, remember:

In the 1990s, the Clinton administration had gone on a big drive to get all the countries of the world, but particularly what they called the big emerging markets of Eastern Asia. It had been on a drive to get them to lift capital controls, telling them that they would get necessary investment money coming in, investment funds coming in.

But in reality, all that came in was what’s called hot money, short term money that invests in asset markets and leaves at the drop of a hat.

And indeed, this is the kind of money that had caused the great East Asian financial crisis and a whole slew of other crises in different markets before then.

Around this time, what then happened is that these countries, unfortunately, rather than impose capital controls, they elected to keep their capital accounts open, but also accumulated reserves in order to have the ammunition with which they could intervene in markets if there was any downward pressure on their currency.

So for example, the Korean Central Bank would keep vast reserves so that if there was a downward pressure on the Korean won, it would use the dollars to buy Korean won and hold up the value of the won. Of course, this meant that they had to increase their dollar reserves. So the share of the dollar reserves went up.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, you’re right. People had to hold dollars in order to interfere with exchange, to regulate exchange markets. And this is what England did for many years.

If you import more because you’re in a boom, the currency would go down if you didn’t have reserves to sell against the dollar. So the dollar was the main measure.

The chart that Radhika just showed actually understates the problem because there’s a little trick there. The trick [is, in the chart, the] dollar is [shown as] a percentage of currency reserves, but foreign reserves are not only in currency, they’re in gold. And if this chart would have shown central bank reserves, it would have shown that gold, especially in the last two years, has shown a rising percentage of currency values.

And that that really is what countries are moving into. They don’t sell gold back and forth to stabilize their foreign exchange markets, as they used to do in the 1920s.

But they’re looking for a kind of an economic system where they don’t want to have to stabilize exchange markets by having the financial system determine exchange rates, but they want to establish stable trade relations among themselves without the financial sector interfering and causing the whole long-term distortion that we’re describing.

RADHIKA DESAI: And that’s a really good point, Michael. And I just want to make one other point about that graph.

So then we talked about how in the 1990s these reserves went up and then what we see is that basically in the new century there has been essentially a decline in the share of dollars as a reserve currency.

And Michael already pointed out one little thing that is ignored by this chart. But some people are pointing out that charts like this also ignore one other thing.

This chart generally takes the reserves at the nominal value. But if you factor in the fact that the dollar has also been losing its value over the same period, then in fact you see much more drastic falls. So not just say from a high of 85% or so to now a high of about 60% or just below 60%, but you would see them coming down to below 50% and even less if you accounted for the actual market value of the dollar.

So, in this way, one indicator is that the share of dollars in global reserves is going down.

So, now you also see stories like this in various financial newspapers. So, this is from the Financial Times. Just one example, “The market in US Treasuries is storing up trouble”, is what Gillian Tett says.

And if we look at the following quotes in that story, she makes a series of points which are really worth noting:

More striking still, these trends recently prompted Janet Yellen, US Treasury secretary, to take the rare step of admitting in public that she is “worried about a loss of adequate liquidity in the market”. On Friday her staff did something remarkable: in a regular market survey, they asked the Treasury Bond Auction Committee (the bankers who run bonds sales) if the government should start buying less-liquid Treasuries, to prevent them freezing up.

…

However, the Treasuries market is also plagued by particular challenges. One is size: US government outstanding issuance has almost doubled since 2015 and quadrupled since 2007. US Treasury market growth has significantly outpaced the growth in bank capital since 2008. This is a remarkable — and little noticed — shift.

Another problem (echoed elsewhere) is that quantitative tightening is raising questions about who will buy government bonds as the Fed stops buying Treasuries. As a punchy paper by economists including Raghuram Rajan and Viral Acharya recently noted, with masterly understatement, this QT is “not likely to be an entirely benign process”. Investors are skittish.

The third problem is market structure. Previously, the primary dealers (ie big banks) kept the treasuries market liquid in a crisis by acting as market makers. But after 2008, a string of regulatory reforms made it expensive to play this role — most notably by demanding reserves against Treasury holdings. As a result, primary dealers’ transactions are now just 2 per cent of the market, down from 14 per cent in 2008, TBAC data shows.

So, first of all, this is just from a couple of months ago [in October 2022].

京公网安备 11010802037854号

京公网安备 11010802037854号