LATEST INSIGHTS

Your Present Location: LATEST INSIGHTS[SCMP] Wang Wen: China's ‘two sessions’ 2024: as GDP gap with US widens, will the ‘East wind’ prevail?

Source: SCMP Published: 2024-03-05

When Chinese leaders bring up the drive for “national rejuvenation” or, more recently, the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” in speeches and official documents, it carries several implications worthy of a closer look.

Most obviously, it articulates a need for China to be restored to its perceived historic state of prominence, but also alludes to room for improvement despite the country’s 2010 ascent to its present status as the world’s second-largest economy. That leaves only one obstacle to be surmounted – the United States, for decades the world’s top dog in terms of gross domestic product (GDP).

Modern China under the Communist Party has long held that such an upheaval was inescapable, though leaders at that time spoke about the capitalist world at large. In 1957, Mao Zedong asserted – echoing a passage from Dream of the Red Chamber – that the “East wind” had already prevailed over the “West wind”. But in terms of economic size, that ambition would only come within reach more than a half-century later.

By 2021 – the year of the party’s centennial – circumstances had changed enough that President Xi Jinping felt confident enough to proclaim “the East rising and the West falling” as a general trend.

Such a tilt in world power would indicate major historical changes in China’s and the party’s favour, but it is far from a settled matter.

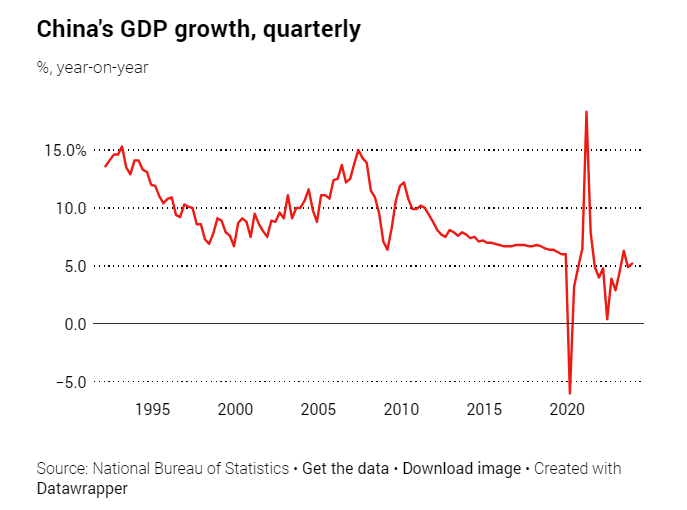

As the first major economy to see a much-desired “V-shaped” recovery following the sharp drop precipitated by the coronavirus pandemic, China had begun that year by pushing its economic strength relative to the US to a new high of 76 per cent, beating the apogees reached by the Soviet Union in the 1970s and Japan in the 1980s.

But subsequent prophecies of an inevitable overtaking – in vogue at the time – now seem premature. Strict Covid lockdowns in 2022 and a bumpier than expected recovery last year have raised questions at home and abroad over whether Beijing still has a chance to challenge Washington’s global leadership, at least in GDP terms.

Building on academic discussions over “peak China”, a phrase coined by Tufts University professor Michael Beckley to suggest the country had reached its expansionary limit, US officials have begun to make their own predictions of their rival’s decline. National security adviser Jake Sullivan said at a Council on Foreign Relations event in late January the moment for a dethroning “may never come”.

In an interview aired last week by CBS News’ 60 Minutes , US ambassador to China Nicholas Burns said many economists believed that the Chinese economy would probably only scrape by with “2 to 3 to 4 per cent growth” annually in the next decade, citing problems unseen in the past 40 years.

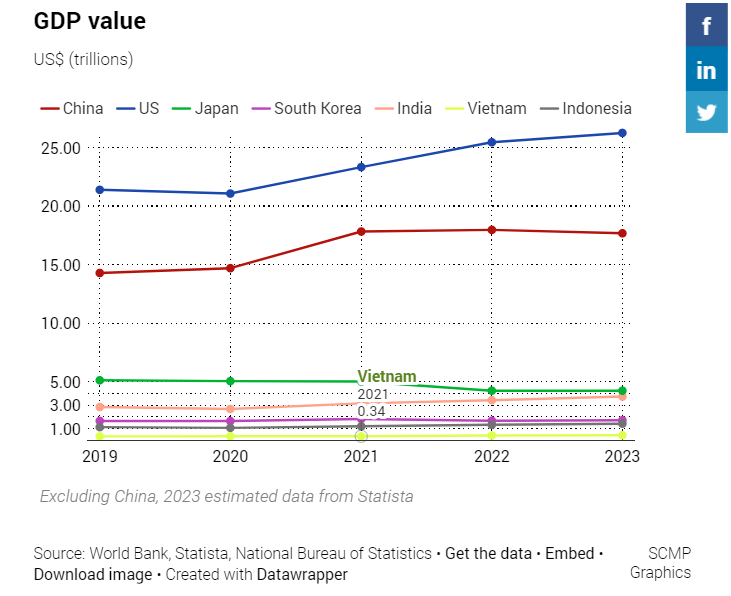

The US economy rose by 6.3 per cent in nominal terms to US$27.36 trillion last year, outstripping China’s 4.6 per cent gain by a comfortable margin and plunging the latter’s relative strength to about 65 per cent.

Beijing has many explanations for the widening gap – exchange rates, inflation and relative purchasing power, to name a few – but analysts said above all it is fighting a war of narratives.

And this battle, they argued, is one Chinese leaders cannot afford to lose.

Chen Wenling, chief economist with the Beijing-based China Centre for International Economic Exchanges, said the bearish takes on the Chinese economy which started last summer – and the consequent capital flight – could be a calculated strategy.

“The badmouthing and short-seller attacks unfolded in tandem,” she said in an interview last week with Guancha, an online news platform. “It’s a narrative war, and by and large a financial war.”

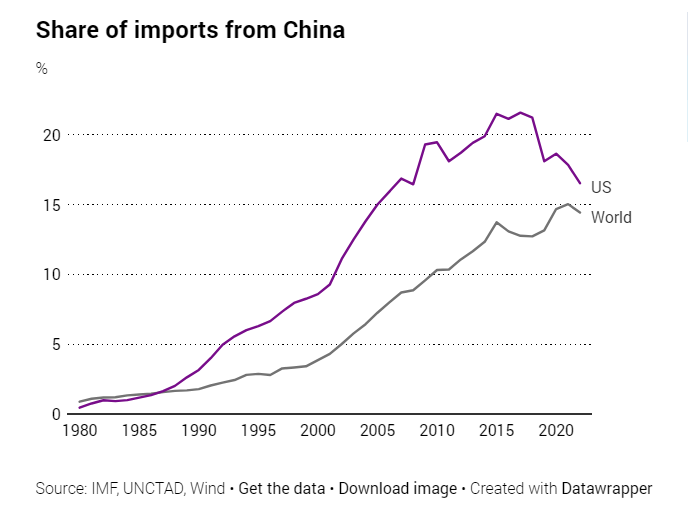

China has taken on greater prominence in the global economy over the past four decades, regularly posting double-digit GDP growth figures and contributing a sizeable portion to the world’s cumulative expansion.

This became even more pronounced after China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, when its door opened wider to international markets.

Its rapid rise – overtaking Germany as top exporter in 2009 and surpassing Japan the next year to become the world’s second-largest economy – buttressed the legitimacy of the Communist Party while quieting theories of imminent collapse that had bubbled up in the wake of the Soviet Union’s dissolution.

Before China’s recent troubles, several overseas institutions estimated it would be top of the podium by the middle of the century, or within 10 years in the most optimistic assessments.

Most notably, the research unit of investment bank Goldman Sachs caused a stir in 2003 by setting 2041 as the year in which China and the US would switch places at the economic table.

“Promoting one’s GDP has become a game of wits designed to impress the rest of the world – if anyone is listening. It’s less about true economics and more about promoting one’s way of life and political system,” said James Zimmerman, a partner at international law firm Perkins Coie and former chairman of the American Chamber of Commerce in China.

“Washington is indeed using China’s current economic woes to emphasise American superiority.”

The world’s second-largest economy has put up its defences in recent months by playing up China’s economic prospects via state-run media organisations.

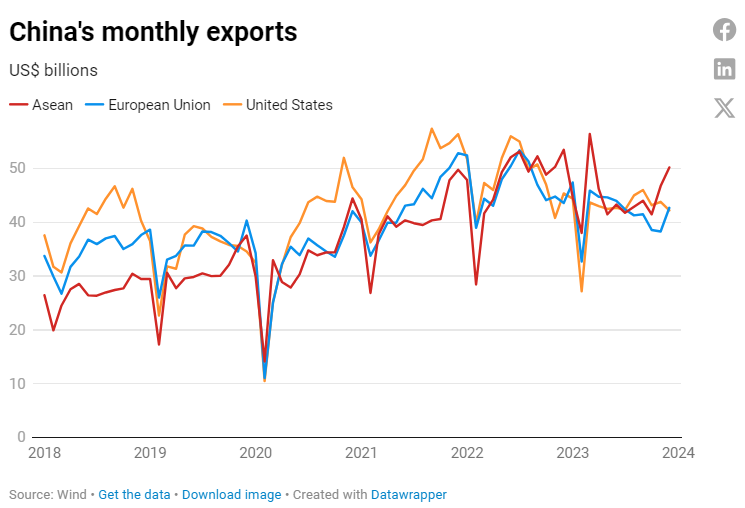

The country contributed around 30 per cent to global growth last year, roughly the same as after the 2008 global financial crisis. It remains a leading producer of industrial and consumer goods, and has held its spot as the world’s top exporter.

In terms of purchasing power parity, a metric used to compare economic productivity and standards of living between countries, China may have surpassed the US as early as 2014, according to a study by the International Monetary Fund.

“Comparing the core economic data of the two countries, we will find that China’s real economy is far ahead of the US’,” Wang Wen, executive director of Renmin University’s Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, wrote in an article on Friday.

He cited the “three new” products – new energy vehicles, solar panels and lithium-ion batteries, keystone goods for the green transition now viewed as potential boosters for growth and prestige – as evidence of how quickly China can achieve and adapt.

Although geopolitical smack talk is nothing new, Wang said, government action to fix domestic problems like unemployment and investor confidence would go a long way in terms of a rejoinder.

A larger challenge will be convincing the developing world, which has relied heavily on China to finance major projects and purchase commodities, including durians, iron ore and crude oil.

As a US-led regime of tech controls, intensifying geopolitical rifts and trade disputes further complicate the environment, analysts said the widened economic gap could lend Washington the upper hand.

“The need for Beijing to revive growth against a bigger GDP gap may mean Beijing will find itself in a weaker position in its talks with the US and other major powers to bring in investments or resolve trade issues,” said Fu Weigang, executive director with the Shanghai Institute of Finance and Law.

Fu, however, sensed more unease from Washington given Beijing’s rapid climb up the economic ladder.

“Washington didn’t care about China’s GDP 30 years ago, but now its president and its ambassador are talking about it,” he said.

“Because the worries are already there and they have to dispel them.”

On the few occasions they have discussed the widened gap with Washington, Chinese officials have largely attributed it to the yuan’s exchange rate and inflation.

The Chinese currency depreciated 4.9 per cent against the US dollar last year, dragging down 2023’s economic output in dollar terms by 0.5 per cent compared to the year before – the first drop in three decades.

Neither China’s state media nor Xi himself have given explicit voice to an ambition to surpass or otherwise replace America’s economic heft.

But the country’s development blueprint for 2035 set a target of doubling 2020s national economic output, which would require an average annual growth of 4.7 per cent for 15 years.

Chinese leaders appear to see rivalry with the US as an all-around contest of national strength – one which includes economic size, technology and value chains among many other fronts – and seem to believe time is on their side.

“Discussions about the GDP race may grab some eyeballs, but this means little to ordinary Chinese,” said Li Xiangyang, director of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ National Institute of International Strategy, at a forum in Beijing last year.

“China should focus on high-quality development and stick to reform and opening up to benefit the people,” Li said, pointing to a waning interest in economic size and great power rivalry.

This week, thousands of lawmakers and political advisers are convening in Beijing to review policy prescriptions to the country’s economic problems. They have much to deal with – weak investor confidence, struggling small businesses, deflationary pressures, demographic challenges, a property market slump and households tightening their purse strings out of job and income insecurity.

The 2024 official growth target has been set at around 5 per cent in a repeat of last year – though China will have to defy the odds to pull it off.

“Now that the West is using GDP to bad-mouth the Chinese economy, Beijing will have [political grounds] to grow the economy bigger to counter the narrative,” said Alex Ma, an assistant professor of public administration at Peking University.

Overseas observers are still wondering what Beijing’s long-term solutions for these issues will be, with the usually economy-centric third plenum of the party’s Central Committee hotly anticipated. By traditional timing, that gathering would have occurred near the end of last year. It has not yet been scheduled.

Zimmerman said Beijing had opened itself up to criticism because it appears incapable or unwilling to take corrective action to address economic troubles, which only makes those troubles more evident.

“China will never surpass the US if it remains on this path, and it’s likely to only get worse,” he warned.

Key Words: Wang Wen, Two Sessions, GDP, the US

京公网安备 11010802037854号

京公网安备 11010802037854号