LATEST INSIGHTS

Your Present Location: LATEST INSIGHTSWang Wen: How has the Belt and Road Initiative changed the world?

Source: Pearls and Irritations Published: 2023-10-02

The ten years of the Belt and Road Initiative has proven that the rise of China has not brought colonialism, disaster, war, refugees, and crises. Instead, it brought the world trade, commodities, tourists, infrastructure, economic growth and civilisation. No matter how Western politicians, media, and think tanks vilify the BRI, they cannot cover up a basic fact—that is, when China is strong, it does not take the old path of aggression and expansion we see in the histories of Europe, the US, Japan, and others.

Time goes by so fast that the “Belt and Road Initiative” has already seen ten years. In October 2023, China will host the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (BRF). Journalists and scholars from around the world have been digesting and reflecting on ten years of BRI. There remain some Western narratives, focusing on certain individual cases or judging from certain angles, that still are not optimistic about the Initiative.

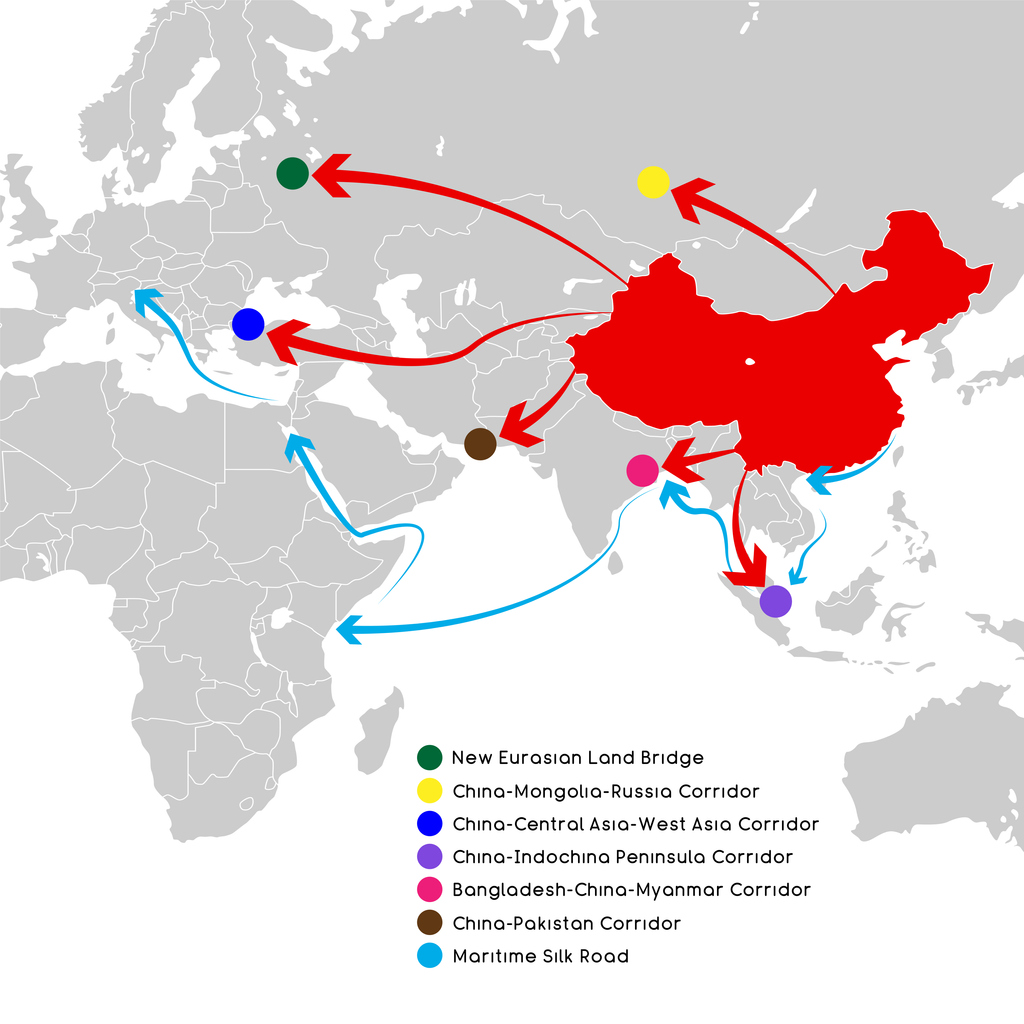

In fact, Chinese President Xi Jinping proposed the “Silk Road Economic Belt” and the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” initiatives (referred to as the “Belt and Road”) in September and October 2013 in Kazakhstan and Indonesia respectively. In the following ten years, we have witnessed significant changes in the world.

From the perspective of foreign strategy, the BRI is the first concept for global cooperation in the history of China’s 5000-year-old civilisation that has both global strategic significance and a clear path for implementation. From the perspective of economic structure, the BRI has revamped China’s past international trade structure which had been overly reliant on the West, and gradually promoted the rebalancing of China’s economic focus. From a cultural perspective, the BRI has completely reshaped the world view of the Chinese in the new era and fostered a global perspective of all-round openness.

But, for the international community, the changes BRI has brought to the world is more valuable than the changes it has brought China.

In fact, while the “Belt and Road” promotes the rebalancing of China’s economic and trade structure, it is also promoting changes to the pattern of international relations and global perspectives. These changes not only influence the actual development and future paths of more and more countries at the level of investment and infrastructure, but also promote the changes and evolution of the international system at the institutional and conceptual levels.

From the perspective of real development, the “Belt and Road Initiative” has significantly improved the well-being of those in the non-Western world, while boosting their interconnectedness with China. As of July 2023, a total of 152 countries have signed BRI cooperation agreements with China. In Africa, China has built more than 6,000 kilometres of railways, over 10,000 kilometres of highways, 20 plus ports, more than 80 major infrastructure developments and 80% of telecommunications facilities. In the past ten years, China has opened more than 1,300 new airline routes with BRI countries. More than 80 countries have seen new bank branches opened or financial cooperation established. China’s average annual outward foreign investment remains at $150 billion, with more and more of China’s capital flowing to BRI countries.

According to statistics, the “Belt and Road Initiative” adds 1.2-3.4% of the actual national total income of the countries along the route. A large number of iconic BRI projects, such as the Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway, the China-Laos Railway, and the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Railway, are completed and operational, to benefit the local communities. The BRI also strengthened the mutual understanding between China and the non-Western world. Each year, more than 400,000 students from BRI countries study in China, while China has established Confucius Institutes, Luban Workshops, and Cultural Centres in more than 100 countries.

From the perspective of the future, ten years of BRI has prompted developing countries to reconsider their choice of development model. In the past, developing countries often regarded the “Washington Consensus” as the only point of reference for their development path. The achievements of ten years of BRI show that the Chinese economic experience, which champions “infrastructure first”, is more suitable to the up-and-coming countries. More importantly, the high success rate of China’s infrastructure production capacity and trade investment, accompanied by a set of operation frameworks that ranges from planning to design, from financing to construction, and from operation to breaking even, has enabled developing countries that have been trapped by a lack of technology and capital to catch up from behind and even surge ahead.

Nowadays, more and more developing countries are contemplating and reflecting in depth: Why has China—once among the poorest of all countries—seen a complete transformation in the past 40 years? Why not choose, learn from, reference, or even comprehensively copy China’s economic growth experience encapsulated in the saying “building the road is the first step to become prosperous”? What is more encouraging is that in the past five or six years, in the face of suppression by the US, China has still maintained medium-to-high-speed growth. Technology companies like Huawei have continued to launch new high-tech products after strict and watertight sanctions. Ten years of BRI cooperation is encouraging the will of the up-and-coming countries to strive for a better future, and thereby improving the balance and fairness of the international community in the fields of technology, trade, and rules.

From the perspective of strategic response, ten years of BRI have been forcing Western countries to reflect on and adjust their foreign strategy. According to incomplete statistics, in the past ten years, Western countries have compiled more than 3,000 various reports on BRI. From the Trump administration’s repeated emphasis on policies promoting infrastructure construction and the development of manufacturing, to the Biden government’s leading role in the launch of the “Build Back Better World” (B3W) at the G7 summit and the unveiling of “Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment” (PGII), all of them are inspired by the BRI, and yet has to compete with the BRI to maintain the so-called “leadership” of the West.

In a Forbes article, it was said that while China issued loans and provided infrastructure to countries lacking in funds around the world, the United States plays the role of a miser. Objectively speaking, global governance headed by the West has made historical contributions, but it has to be said that, in the 70 years following the end of WWII, and especially since the end of the Cold War, the negative impact the West had on the world far outweighs the positives. Nowadays, Western countries are reflecting on themselves, increasing their efforts to cooperate, in an attempt to compete with China. If it can actually help developing countries, it must be said that it is also an unexpected surprise brought by the ten years of BRI.

What is regrettable is that the West attempts to compete with the BRI through strategic reflection, which is full of lies, slander and speculation. A case in point is the talk of debt in Western media and think tank circles.

In fact, China has promoted infrastructure construction through foreign policy loans, reducing the cost of current economic transactions with highways, railways, and ports to improve the efficiency of economic activities, which then drive up the land and real estate prices in the region. The local government can then easily repay the various debts under sovereign guarantee. This logic, which might be called “BRI Economics,” surpasses the theoretical assumptions and rationale of Western economics, and also reflects the powerlessness and absurdity of the Western attacks on BRI debts.

However, criticism and besieging of the Belt and Road Initiative has been popular in the West for ten years, and will remain popular. This reflects the long-term international challenges facing BRI.

It hasn’t been long since the Chinese first made contact with the world and participate in global governance. For thousands of years, China was isolated and confined to the east of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and the western desert, and only maintained contact with other countries through the land-based and maritime Silk Road. At that time, whether it was the Han or Tang Dynasties, or the Yuan, Ming, the Silk Road was busy exactly when countries in the European hinterland were at the height of their civilisation and economic prosperity. In 2013, when China ranked as the world’s second largest economy, it launched the Belt and Road Initiative in the name of the “Silk Road” to revive the historical memory of the common prosperity of the ancient civilisations, showing the aspiration of a rising global power to mutually beneficial, peaceful and win-win cooperation, and, ultimately, to the joint rejuvenation of the world.

No matter how Western politicians, media, and think tanks vilify BRI, they cannot cover up a basic fact—that is, when China is strong, it does not take the old path of aggression and expansion we see in the histories of Europe, the US, Japan, and others.

The ten years of the Belt and Road Initiative has proven that the rise of China has not brought colonialism, disaster, war, refugees, and crises. Instead, it brought the world trade, commodities, tourists, infrastructure, and economic growth and civilisation. This has never been achieved by Western countries in the histories of their rise to power.

“One Belt One Road” new Silk Road concept. 21st-century connectivity and cooperation between Eurasian countries. Image: iStock

Of course, new things will inevitably be accompanied by bewilderment. During the tenth year of Reform and Opening up, even mainstream academics in China were arguing about whether the “market” was socialist or capitalist in bewilderment; now, after 45 years of Reform and Opening up, no one suspects its great significance any longer.

The Belt and Road Initiative is only ten years old. For a grand strategy like BRI, ten years is too short to fully assess its impact, but it has already shown its extraordinary significance. The BRI is willing to make time its friend. In 20, 30, or 40 years, or more, maybe everyone will then come to admire the greatness of the Belt and Road Initiative in the same way we have come to admire the greatness of China’s Reform and Opening-up.

Key Words: Wang Wen, BRI, Changes

京公网安备 11010802037854号

京公网安备 11010802037854号