LATEST INSIGHTS

Your Present Location: LATEST INSIGHTSRadhika Desai: Did big banks take over US Treasury? Radhika Desai & Michael Hudson discuss banking crisis

Source: Geopolitical Economy Hour Published: 2023-03-25

Economists Radhika Desai and Michael Hudson discuss the US banking crisis and the effective privatization of the Treasury in this episode of their program Geopolitical Economy Hour.

Transcript

RADHIKA DESAI: Hello everyone, and welcome to the sixth Geopolitical Economy Hour, the fortnightly show on the political and geopolitical economy of our time. I’m Radhika Desai.

MICHAEL HUDSON: And I’m Michael Hudson.

RADHIKA DESAI: As you know, the last time when we closed we were scheduled to do our fourth and final show on the subject of dedollarization. However, as you know, the best laid plans can be thrown awry by, as Harold MacMillan said, “Events, my dear boy, events.”

Since we published the fifth show we’ve had what looks like the biggest financial crisis since 2008 and 2020 on our hands, with the usual flurries of bailouts and emergency actions, which in other words amounts simply to a socialism for the rich.

So of course Michael and I had to devote our show today to that topic.

So we’re going to talk about how this crisis is no isolated crisis but really another chapter in the long unraveling of the US financial system — an unraveling in which the really public character of banking — that is to say, the fact that banking is always meant to be a public utility becomes manifest under the pretense that it can be maintained as a private system.

So the crisis has by now been declared as over by some, and the markets seem to be calm, but nevertheless they have been extremely rocky.

Madame Yellen said on Thursday March 16th to the Senate Banking Committee, “I can assure you […] that our banking system is sound.”

So basically she’s saying, “Banking crisis? What banking crisis?”

But of course, Michael, you and I have a different view, don’t we?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well what she said were words that you never want to hear from a regulator — that everything is sound. That means things are falling apart.

And her next words — the rest of that sentence — were that “Americans can feel confident that their deposits will be there when they need them.”

In other words, what Yellen said was that she actually acknowledged that the United States banking system is insolvent. She said, “Forget the promises that we’re going to limit deposit guarantees only to $250,000. We are now guaranteeing all depositors in the system.”

The banking system is now a branch of the US Treasury with the whole value of the US Treasuries behind the banking deposit — there’s no more risk essentially.

It would appear at first glance that she’d nationalized the banks.

But really what happened was that — it wasn’t reported in the newspaper, [but it’s almost as if she’d] just taken a mid-level job at Wells Fargo — maybe it was at Citibank — saying the Treasury is now a subgroup of Wells Fargo, Chase Manhattan, and the large banks, [pledging all its credit so that uninsured depositors will not take a loss.]

The banking system has cannibalized the Treasury and mobilized the whole of Treasury for its banking.

People had, for a long time, wanted the idea of public banking. They wanted banking to be a public utility. But now the Treasury itself has become privatized as a banking utility.

Given the sort of widespread awareness of insolvency, when S&P downgraded the entire banking system last week, the Treasury essentially is making a commitment that it will back up whatever the private banking system has done.

“We’re not going to regulate it anymore because, after all, we never have been regulating it for the last twenty years.”

This is supposed to make it more efficient. Get government out of the picture. Just turn everything over to the big banks to manage.

A public bank would have — why do we need the banking system in this case? That really is what everybody should ask, and what I think our show discussion today is going to be about.

A public bank has no reason — logic — to speculate in derivatives. A public bank wouldn’t have to invest in Treasury securities because it would be part of the Treasury.

It wouldn’t lend for derivatives. It wouldn’t make take-over loans. It wouldn’t do all of the things that have led to the collapse not only of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank but to most of the banking system, with its reported $630 billion of losses on its capital account — its assets that it doesn’t have to report because of the way in which bank reporting is based on fantasy prices, not market prices.

RADHIKA DESAI: Quite so. Michael. You put it so well. Because basically, when you can’t have banking as a public utility, then inevitably what happens is the government becomes a private utility. That’s exactly what’s going on.

And of course, because you’re trying to make something into what it isn’t, and in fact cannot be, the process is bound to be fraught with great contradictions.

So of course you are absolutely right to point to the fact that Madame Yellen has essentially bailed out the depositors — extended deposit insurance to all the depositors, not just up to the $250,000 — of a couple of banks.

But what’s also really interesting is that she has had to stop shy of extending it formally to all banks. All they’ve said is that they will try to bail out other banks if they are systemically important. So we’ll just have to see how it rolls along.

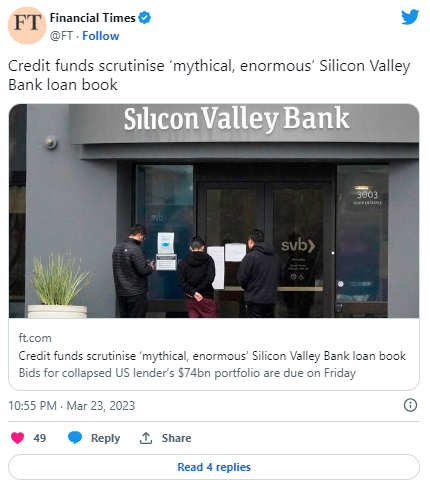

Now, what has emerged in the last couple of weeks is that, contrary to what some have argued — which is that SVB should have been bailed out because it was some sort of a “good bank,” that it was investing in the “cutting edge” of American industry and investing in production — in reality what we’ve discovered is that SVB’s banks assets are of much more dubious value. That the federal agency charged with selling and dissolving it cannot find buyers, either for the whole of the bank, or banking assets.

The Financial Times in this story reports that the largest portion of the loan book of Silicon Valley Bank, [which] was $41.3 billion at the end of 2022, consists primarily of so-called “subscription lines” which SVB offered to private equity and venture capital funds.

Such loans are extended basically to tide over a fund between the time it buys a company, or makes an investment, and when the fund receives the money that has been promised — of which of course there are no guarantees.

So such loans are always very low-yielding; they are not even rated. And they are now considered too risky by financial institutions. That’s the bulk of [SVB’s loan book].

And then another part of SVB’s alleged investments amounted to speculation — what we may call “crony lending” — lending on a rolling basis to already rich people and their private funds to enrich them so that they can enrich themselves through dividends and management fees even when they are not making very much money.

And the repayment is postponed [until] the unlikely event that there is a successful IPO. These were the depositors that got bailed out.

So honestly the “all is well” message is definitely not very credible. In fact what we are seeing — and of course we’ve seen that [Jerome] Powell has repeated the message of Yellen — he said the banking system is sound and resilient and deposits are stable and he claimed the crisis has been stemmed by the decisive action of the Federal Reserve and the Treasury

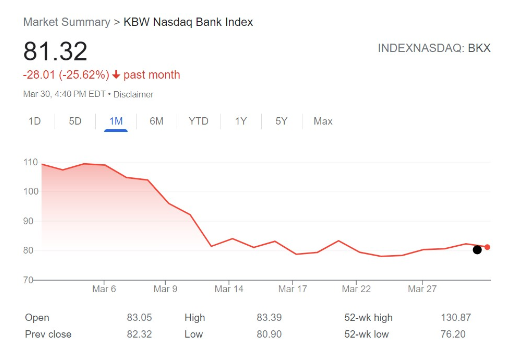

But look at this [graph] of the KBW index — a major banking index.

You see that banks have been sliding over the past month and they remain quite low. They are not recovering. The investors are not assured. The public is not assured.

And in this context it’s also very interesting that the Stanford Business School is reporting that the US banking system’s market value of assets is two trillion dollars lower than suggested by their book value.

So this is — and this low level declined — they have dropped by ten percent in the last little while. So this is really quite a serious matter.

Obviously this doesn’t mean that everybody’s going to run and that these losses will be realized, but it shows you how precarious the system is.

So the Federal Reserve in the meantime remains caught in this pincer movement between monetary stability and financial stability and has therefore produced a compromise of a 25 [basis point] rate hike.

This is the very difficult — and very troubling situation — so Michael lets you and I delve right in.

So really what we want to talk about today is the unraveling of neoliberal financialization.

So for the last two decades, basically, US authorities have acted like the policeman in the film Casablanca who is shocked to find there is gambling in the casino.

This is exactly what’s going on. This is what Alan Greenspan did when he was testifying about the 2008 crisis. He said, “I thought markets were very well and I was shocked to find out that they are not working well.” Ben Bernanke has done the same thing.

Every time there’s a crisis, the authorities claim to be shocked once again. And the fact of the matter is that we simply cannot take them at face value.

The fact of the matter is that the US banking system is not only not sound today, it has not been a seriously functional banking system since at least the 2000 dot-com crash, if not even earlier than that.

When the United States dollar-based financial system made the transition to ultra-low interest rates — chiefly because financial authorities realized that asset markets — the inflation of asset bubbles, particularly the real estate bubble — was the only thing working in the US economy, so they decided to give it full rein.

And so low interest rates were designed to do that. And so this banking system has been failing in its most fundamental function of assessing risk. In fact it has become based on excessive risk.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well when you say “risk” it’s really arbitrage.

There was no risk of non-payment in the Treasury securities that the bank held. There was not even a risk of non-payment for the mortgages that it held.

The risk is simply the fact that interest rates went up. And the fact that, for years, Silicon Valley Bank, like all the other banks, only paid depositors about 0.2% on their savings.

Any of you who had your money in the bank, there was no way that you could get a higher rate than about 0.2%. Well, the bank thought it was making a profit because here it was paying depositors that little rate, and it could get 1.8% on government bonds.

Well this is lower than government bonds really had ever been, so that there was a 100% probability — no risk there — 100% loss in the market price when the Federal Reserve — when Mr Powell said, “We’re going to begin to raise the rates.”

“We’re going to raise the rates because we need to slow the economy so that wages are going to go down” — as we discussed before.

And when the government says it’s going to raise the rates, he didn’t realize that he would not only be hurting labor but he would be hurting the banks, because if they have their reserves held at very low-interest bearing securities, at 1.8%, when rates go up to 4% obviously that means that the value of the old government security 30-year bond falls to about 70 cents, maybe 65 cents, on the dollar.

Well nobody would have cared about this if deposits hadn’t been withdrawn.

But because the banks are still only paying 0.2%, anybody could take their money out of the bank savings account and buy a two-year Treasury note that would yield over 4%. So why would they leave the money in the bank?

In fact Americans begin to withdraw their money from banks all across the country. And once they withdrew [the money], the banks had to actually raise the money to pay them by selling these bonds that they bought at a low yield.

And all of a sudden they realized that, “Wait a minute. What we were carrying on our books as worth 100 cents on the dollar is really only 70 cents on the dollar.”

They had to take a big loss because under the rules of reporting, banks report what they paid for the assets, not what the assets [are] actually worth on the market.

Because if they reported what their assets were really worth, you’d see today that the banks are broke.

That’s why the Treasury has said, “We will bail you out. We’ll take over the banking system. Even though the private banking system has outlived its function. Even though the private banking system cannot survive if interest rates go back to normal. We’re going to keep bailing them all out.”

And that basically is what’s happened. So the kind of risk was a result of the Federal Reserve’s own policy, and it’s a risk that affects the entire banking system today, not just Silicon Valley Bank.

RADHIKA DESAI: So true Michael. And you know, this also — just to remind you, we had a show a few shows ago on inflation and what has caused this inflation.

One of the things we pointed out is that the Federal Reserve is not going to be able to continue to raise interest rates — not because it cares about American workers — it would dearly love to raise interest rates in order to crush the working class, crush their employment prospects, crush their wages, etc. — but it cannot.

It cannot — not because it is so tender-hearted towards American workers and workers elsewhere for that matter — but [because it is] tender-hearted towards the filthy rich in the United States.

So the banking system is based on excessive risk, as we’ve just been saying.

It has also been investing — not in production, which is what your Economics 101 textbook tells you it should do — rather it has been investing in everything else — in real estate, in consumption loans, in government bonds — which by the way finance tax cuts — and not government investment in anything worthwhile. Or government spending for that matter in anything worthwhile. And in other speculative products, including asset-backed securities, derivatives, and so on.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well the banks really have been lending for speculation, as you point out, on financial securities and making arbitrage gains. You borrow at a low rate and you buy something yielding a higher rate.

You make money off asset-price inflation.

And the Federal Reserve’s $9 trillion of quantitative easing has simply been aimed at raising stock prices, bond prices, and real estate prices. And that’s how banks have been making their money.

The effect on consumption has been to load down households and also industrial corporations with debt, and it’s to finance takeovers that use corporate profits to support stock prices.

Corporations have been borrowing from the banks simply to buy their own stock, because their own stock pays dividends that are higher than the low borrowing rates.

They’ve been borrowing even to pay out as dividends, because if you borrow money, you pay it as dividends, that’s going to raise the stock price temporarily. Obviously the loans have to be repaid at a point.

And if you have private capital taking over a company like Bed Bath & Beyond, it’ll privatize the company, make a loan to [that same] company, take that loan and then pay themselves a special dividend for management, leaving the company a bankrupt shell.

So you could say that the role of the banking system is to bankrupt corporate industry and to lock in the transition from industrial capitalism to finance capitalism.

Really it’s suicide.

RADHIKA DESAI: Exactly. And this kind of finance capitalism essentially is predatory. Predatory essentially upon workers’ wages and taxpayers’ revenues.

Because — either directly or through government payments — we are paying for — ordinary people are paying for essentially — the banking system has been transformed into a machine that transforms a goodly part of our taxes and a goodly part of of our wages into further payments to themselves.

This is a predatory banking system. In fact not only is it predatory, but it also tends to strangle the productive part of the economy.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well I think then we need to define “predatory” and as you said, it basically means “unproductive overhead the non-financial economy has to bear.”

I think a predatory loan is one that does not provide the means to help the debtor repay its creditor.

For instance, people believe that they’re getting rich by borrowing from the bank to buy a house whose value goes up, but the value of housing going up is because so many people are borrowing that the housing is worth whatever a bank will lend, and it’s all been bid up on credit.

So what’s really gone up is the housing debt.

People say, “My house is worth a lot more.” But the equity that people have in their houses has been falling and falling and falling as the economy becomes more debt-leveraged.

So it’s not simply wages and profits that banks want. What they want is to transform property into financial gains. It’s all about capital gains. It’s about asset-price inflation that they love, as opposed to wage-inflation.

RADHIKA DESAI: And actually that reminds me this is really a system that is about profiting without producing. That’s what they are on about.

So it is also therefore very speculative. It’s based on inflating asset bubbles, which of course has been the result of two decades of low interest rate policy — what people call the LIRP for Low Interest Rate Policy or ZIRP, which is Zero Interest Rate Policy.

And the result is that today there is essentially a bubble in practically every asset market.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Yeah, that’s what a zero interest rate policy was all about. They said, “We have to reinflate the price of stocks, bonds, and real estate.” Because the banks after 2008 were — back then, negative equity. They couldn’t cover what they owed depositors.

The way of saving the bank was to vastly raise the price of housing in the United States and raise the price of buying a retirement account.

RADHIKA DESAI: Yeah, and then in addition we have seen a few other things as well. We have seen the financialization of productive corporations.

Once you create such a vast and powerful financial sector, the few remaining productive corporations basically throw in the towel. They say, “If you can’t beat them, join them.”

So essentially they also develop financial arms. You’ve probably heard of the saying that GM makes more money lending you money to buy cars then it makes building and selling you cars. GM Financial is bigger and more powerful than GM itself.

So this has been of course the trend that has been noticed throughout the present century and even going back a little bit before that.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Even Macy’s used to make more money by getting credit cards for Macy’s customers than they made actually on the store.

It’s as if the whole objective of corporate industry today is to get consumers to run into debt and make money off the interest that you charge for consumers rather than to make profits.

So a economic analysis that focuses on profits made by employers exploiting labor misses the point that there’s much more income to be made by financializing than by industrialization, and that’s why the people who basically run the economy — the management’s been shifted from Washington to Wall Street — say the money’s to be made in financialization and not industry.

That’s why we’ve been deindustrializing and painted the US economy into the corner that it really can’t re-industrialize without replacing the banking system that is in the middle of showing that it doesn’t work.

RADHIKA DESAI: No, exactly. And then we also see that the kind of economy that has now emerged as a result of decades of policies that have encouraged financialization and discouraged production is that we basically have an economy of corporations whose balance sheets don’t bear much scrutiny.

And that is why you’ve seen the rise of private equity, which means that you can have corporations that do not have to make their accounts public — that are not kept accountable by any sort of public scrutiny.

So the risks here are so great that more and more companies cannot be listed publicly and have their balance sheets scrutinized publicly.

Therefore all the lending that goes to these outfits, again, is lending that takes place in the kind of crony lending fashion that we have already discussed. And this is the kind of structure that has created the astronomical inequality that we have all noticed in the recent past, particularly over the COVID period, but it goes back a long way.

In fact when Thomas Piketty wrote his big fat book on inequality [Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013)] he actually missed the trick because he blamed rising inequality on capitalism alone. And I’m not saying capitalism is innocent, but this kind of financial capitalism has been primarily responsible for transferring wealth from the ordinary people to an extremely small filthy rich elite.

And in this system, the financial system has been a major aid to this process.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well most people, when you think of inequality, the way it’s shown in the newspapers is, they think of inequality of income — the wealthy people are making more income.

But by far the main source of inequality is that of wealth. It’s on the balance sheet. It’s assets and debts.

And if you looked at wealth, half of Americans have no net worth. Zero net worth. Compare the zero to the enormous wealth that the 1% has made since 2008 as a result of the asset-price inflation — that’s where the inequality is.

That’s what the aim of ZIRP was, to inflate the asset market.

So people think of prosperity as being when the value of their stocks and bonds go up, and they pretty much ignore the fact that this is much more overshadowing than just income.

There was a point in the 1980s, and again much more in the 2000s, where a worker could go, take out a mortgage, buy a home, and in one year the price of the home’s increase would exceed what the worker could take home during the entire year.

Imagine how this affects — by the fact that the upper 10% own maybe two-thirds of the stock market and the bond market. That’s where the real source of inequality is.

And you have to look at the balance sheet of finance capitalism, not at the dynamics of industrial capitalism that’s being replaced by this financialization.

RADHIKA DESAI: You know, what you say Michael reminds me. If you look at — a lot of us, we love to drive at how much doctors may make, or how much some people who are employed may make, whereas the rest of people make so little.

But the biggest inequalities of income are not between different sections of those who make their money through work.

Yes, they are great, but they are nothing compared to the differentials of incomes between those who make money through work, and those who make money through wealth. And you can see charts about this. This is what it’s about.

So anyway, what we are trying to say is that the financial system, even before 2023, even before 2020, even before 2008, was already unsound.

And we have simply seen a demonstration of the unsoundness of the system. So basically, all of these bubbles that we are seeing — they are now waiting to be worse. Because right now, as a result of decades now, almost two decades of low or zero interest rate policy, we today have an “everything bubble.”

Every asset market is in a bubble situation, and the recent interest rate hikes have been the pin. They are bursting the bubble. The prices of assets of all sorts — not just government bonds which were involved in the SVB collapse, but also derivatives, real estate, commercial real estate — every form of assets [is] declining.

SVB was invested of course in long-term government bonds and I won’t repeat — Michael’s already explained very nicely what went wrong there. And many progressive thinkers were arguing that Silicon Valley Bank was a good bank, providing patient capital and whatnot.

But in fact, as Pam and Russ Martens of this wonderful website Wall Street on Parade which you should check out if you’re interested in these things — as they pointed out, Silicon Valley Bank was basically a pipeline that moved extremely speculative types of investments towards IPOs, many of which of course never materialized.

But the cost of those — and that cost included the lavish lifestyles and the immense wealth agglomeration of the people involved — were financed by institutions like Silicon Valley Bank.

Earlier, cryptocurrencies also were going bust. There has been a silent crash in equity and real estate prices and commercial real estate prices. They have all been crashing.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well what you’ve described is what was called “economic rent” in the nineteenth century. What used to be the landlord class that was running society is now the financial class.

They make money basically by what used to be paid as rent. Under the old aristocracy that emerged from feudalism, people would pay rent to the landlords — the “ground rent”.

Now that housing has been democratized, the rental value is paid to the banks as interest. So instead of being a rentier class based on “land rent”, we have a rentier class based on interest and on making money financially in the way that you said. (Ground rent and land rent are interchangeable — Ed.)

The banks don’t lend out their deposits for industrial development. They don’t lend them out to build factories and new means of production. They lend them out to buy existing factories and break them up and turn them into gentrified housing to make profits.

It’s sort of a travesty to compare what’s actually happening to what is reported in the textbooks. And of course it’s very hard to have a huge financial superstructure [without] an industrial base. And if you have a superstructure on a teeny base, at a certain point it’s going to collapse.

And that’s finally what we’re saying today. The idea of a post-industrial economy making money purely on financial engineering instead of industrial engineering ends up with more claims for payment than the economy can pay.

That’s been the theme of all of our shows and that’s exactly what you’re seeing today. Ponzi schemes work until somebody wants to withdraw their money. And once you say, “Okay you say we’ve been getting rich, now we’ve put all this money into this scheme, let’s try to withdraw” — all of a sudden we’re told it’s not there.

You’re seeing Mr. Macron in France facing riots when he’s trying to say, “Well, we can’t afford to pay social security because the banks needed more money for the bailout, so we’re going to extend the retirement age.”

I’m waiting for Mr. Biden to go back to his program of a decade ago and say, “We’ve got to cut back Social Security, got to cut back Medicare because we’ve had to use the money for the bank bailout. I’m sorry there’s no money, and now that the Treasury is part of Citibank and Wells Fargo we have to do first things first.”

Regulatory capture

RADHIKA DESAI: This is absolutely right, Michael. And this is one set of problems — there’s excessive risk, there’s this Ponzi character.

Now, you’d think that the Federal Reserve and the government exist to keep oversight on this, to ensure that these banks are regulated, that they don’t get into trouble. So why do they get into trouble? The reason is because the system is actually riven with what’s known as regulatory capture.

Which is essentially a fancy way of saying that you are hiring the fox to guard the chicken coop.

The fact of the matter is that the Federal Reserve, which is supposed to regulate, is itself captive of those it is supposed to regulate.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, the regulators don’t regulate. If you look at what’s happened to Citibank, Wells Fargo and Chase. They were told by the regulators, “You’re on probation. You’ve broken the rules. Don’t break them again.”

They break them again. Again and again they break them. The Federal Reserve does nothing.

The Federal Reserve of San Francisco sent out warnings to Silicon Valley Bank, saying “Hey your balance sheet can’t cover your deposits. You’re in negative equity, and we’re drawing your attention to that.”

And the reply from Silicon Valley Bank, “Yep we’re paying attention to it. So what? You can watch television. You can pay attention to us.”

There is no regulatory apparatus, and no regulatory apparatus can be put in as long as the banks get to nominate the regulators. They have one of their lawyers go and act as a regulator.

Sometimes the regulators are appointed by Washington, but they’re appointed by the heads of the Financial Committee and you become a head of the Financial Committee by contributing money to the Democratic or Republican Party leadership. And the committee head [positions] are sold off for who raises the most money.

So all the banks have to do is give their lobbyists enough money to buy the position as head of the Financial and Banking Committee so that they can appoint regulators from the banking system.

As long as you have the Citizens United rule of essentially putting politics up for sale, the banks are going to take over the regulations.

So again, what’s happened is that instead of the banks being nationalized, the Treasury has been privatized by the banking system. That is sort of the ultimate victory of finance capitalism, but the result is that it’ll destroy industrialization and what used to be industrial capitalism in the United States.

RADHIKA DESAI: Exactly, indeed, Michael — as your new book is going to argue, [financial capitalism] is going to destroy civilization itself.

In The Collapse of Antiquity, Michael traces the whole history of the current patterns of financialization back into antiquity and connects it indeed with the collapse of antiquity. So do check it out, it should be available on Amazon now.

But to return to our point now. Michael, what you say actually reminds me so much of the famous novel Lord of the Flies.

Because again, when you think about the regulators, the idea is that there are regulators and they regulate the banks. So there are some adults in the room that are going to make sure nothing goes wrong. But actually there are no adults in the room — everybody is one of the kids who is essentially going to egg the other kids on into ever greater hijinx, and that’s what we are seeing.

There is a long history of regulatory capture, and let me just read off some of the major moments in this.

So the Federal Reserve has been colluding in deregulation since the 1990s. And in what we may call the original sin of this financial system, which was the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, which divided banking into investment banking and commercial banking and provided deposit insurance only to commercial banking which it then proceeded to regulate fairly heavily.

Investment banking could do whatever it liked, but whatever losses it made, it was losing money on its own dime — nobody was going to help it.

But the repeal of Glass-Steagall essentially has muddied all the waters and it has allowed the Federal Reserve to step in and say, “Okay we can bail everybody out.”

And the repeal of Glass-Steagall, the way it happened, is also very interesting. Because Citicorp merged with Travelers Group — an investment bank with insurance interests — to create Citigroup, and this challenged the Glass-Steagall boundaries — the red lines that were drawn between investment banking and commercial banking, insurance, etc.

So the situation this produced was that either they had to comply — that is to say break up and sell off parts of the merged banks so that they would once again be compliant with Glass-Steagall within a year or two.

Or Glass-Steagall had to be repealed. And now, get this. The regulator Alan Greenspan bet that the industry would get to do whatever they liked, and the regulation would be defeated, and he won.

And the repeal of Glass-Steagall in 1999 has undoubtedly laid the basis of the 2008 bubble and today’s multiple bubbles and everything that has happened — the quantitative easing, the ZIRPs, the LIRPs, everything.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well that’s right. You remember when Drexel Burnham went under in the 1980s, it didn’t matter. There was no crisis in the banking system. The customers of Drexel pretty much thought so. The stockholders were wiped out. The Fed didn’t say there’s a big crisis.

But then, once you had the brokerage companies merged with the banking companies, the brokerage companies took over the banks. It was the financial, speculative part of Citibank that took over. All the banks bought brokerage companies and essentially you had the transition from old-fashioned banking, of just lending out money, to stock market speculation.

And the result is that you have the situation you have today. That’s why Moody’s ended up downgrading the entire banking system, because now it’s all a stock market speculation basically. It’s not a banking system.

RADHIKA DESAI: And just to reel off a few other such instances, the Federal Reserve’s concealment of the real extent of the bailout of 2008 is also very interesting.

This is generally confused with the Troubled Asset Relief Program (the TARP), which was actually quite modest — it was $750 billion.

They realize this is the case, and then put the extent of the real bailout — which was essentially Federal Reserve money printing — at $7 trillion.

However, economists at the Levy [Economics] Institute [of Bard College] have in the last few years actually tallied — if you put together all the different emergency programs that were rolled out by the Federal Reserve in the aftermath of 2008 — it amounts to 29 — get this, $29 trillion.

So if you just Google the words “29 trillion” I’m sure you’ll find the relevant paper.

There was also the Federal Reserve policy reversal after the 2015 temper tantrum. That is to say, when the Federal Reserve decided that it was going to tighten up monetary policy a little bit — stop doing quantitative easing and do a little bit of quantitative tightening — the market had a tantrum, and the Federal Reserve essentially capitulated to it.

There was the Trump-era loosening of regulations under the already weak Dodd-Frank Act, because the Dodd-Frank Act was supposed to be a replacement for Glass-Steagall, but it was nowhere near that, and even that was weakened.

And by the way, in this weakening the Silicon Valley Bank CEO Gary Becker played a major role.

Further, there was a concealment of the 2019 bailout of the repo market — the market in which banks borrow overnight from each other. There was a big crisis in that. Interest rates were going up. We don’t fully know what happened yet. The Wall Street on Parade once again has exposed this but it still remains to be found out exactly what happened.

There was the 2020 Federal Reserve trading scandal in which Federal Reserve governors used insider information about which banks were going to profit from which bailouts, and used this in trading, which was also extensively reported.

There was the Federal Reserve bailout of 2020 itself which was now extended to productive corporations — not because the Federal Reserve cares about productive corporations, but because these productive corporations and the assets that they created for the financial system were very important for the financial system.

And finally there was the Federal Reserve doing everything possible to create and maintain the unsound structure of US banking today.

What you see as the US financial system is actually the Federal Reserve’s baby, and this is the one that has been downgraded by Moody from “stable” to “negative” — the entire US banking system, which prides itself on being the most advanced and sophisticated financial system in the world.

So decades of these practices have now come home to roost as interest rates are going up and created the classic dilemma between maintaining monetary stability — that is to say curbing inflation — and maintaining financial stability.

The Federal Reserve is caught between these two demands, and it cannot achieve both of them at the same time, and that is why the Federal reserve has opted for a 0.25% increase so that it looks like it is still combating inflation but this increase, combined with its backstops, somehow tries to save the financial system from its own misdemeanors.

So this is the point at which Yellen has stopped a more pervasive run on the banks by announcing that there will be money for systemically important banks, etc.

But here she’s also caught, given the anger that people still feel at the bailout of 2008. She cannot be shown to be using taxpayers’ money in order to bail them out. So what is to be done?

There are a number of other measures that have been proposed.

One of them is simply to let the markets do their work. If banks are going to collapse, let them collapse. Let there be no bailout.

Bailout alternatives

MICHAEL HUDSON: That means taking them over. And you had that, I guess, with [Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Company].

Taking them over — how is the government going to run them? Is it going to take them over and say, “Okay, your way of doing business hasn’t worked out. We’re now going to be running it as a public bank, as a state bank — making loans for purposes that banks used to be supposed to be making [them for] — for sound mortgage loans, not for speculative purposes.”

Or, are they just going to take them over and then say, “Well here’s a weak bank. Let’s sell it to Chase Manhattan or Citibank. Let’s sell the weak banks to the strong banks so that we’ll end up with maybe five banks in America like Canada has.”

What is the government going to do when it folds up a bank? The pressure is that they’re going to just give them to the big banks and essentially the big banks will end up running into the same problems that led the small banks over [the cliff].

And the government will be paying — not with taxpayer money, it’ll just create the money to do that.

RADHIKA DESAI: Of course Michael, what you’re saying is probably what is likely to happen, but I should say that the people who are suggesting [letting banks collapse] are not suggesting what you’re saying.

They are suggesting that the banks should be allowed to fail because not allowing banks to fail has created moral hazard.

Now I agree with you this will not happen, chiefly because of the problem we’ve already talked about, which is regulatory capture. The financial sector will not stand for it, and the Federal Reserve and the alleged “regulators” will do exactly their bidding — which is that if they become unviable then they will be bailed out.

But that is one point that is being made.

And by the way, I should add that you refer to Too Big To Fail (TBTF). Too Big To Fail was first used as a principle to bail out a bank when Continental Illinois went bust in 1984 thanks to its exposure to a lot of Third World debt in particular. And that was the first time it was used, although then it remained quite episodic.

But today [TBTF] has become much more systemic.

Anyway, the second proposal that has been made is that all bank deposits should be covered under the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

Now there are two problems with this.

Number one, there are many Republicans who will oppose this, and the Biden administration is not going to be able to pass the relevant legislation if there is a sufficiently sizable number.

[Number two], they will also require increasing insurance premiums that the banks will have to pay if the financial sector is going to have to collectively pay for its own failures, and this will be resisted by the financial sector itself.

Of course, there are other more severe options.

People have said, increase reserves; decrease leverage; convert debt into equity, especially if the bank shares sink below a certain point, some of the debt becomes equity, which means that people who have invested in this will stand to lose money. [Essentially converting debt into equity means that lenders become owners and they partake to a greater extent in the risk of the firm, losing the seniority of bondholders over shareholders and risking losing more if the firm goes bankrupt. — RD]

They have also proposed that you should strictly enforce Mark to Market (MTM) accounting — penalize the management of failed banks.

So these are many such proposals, but all of these will in one way or another be resisted by the financial sector itself.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well Martin Wolf has suggested moving [to] a 3:1 leverage ratio instead of the 10:1 or 20:1 ratio now common.

In other words, the banks shouldn’t be able to make such high loan-to-value loans. That would hold it in.

And he’s also mentioned the “Chicago Plan” — basically turning the banks into savings banks, which is what they were originally imagined to be.

They won’t create credit. Take away their ability to create credit, because they stopped creating credit for useful public purposes.

100% reserves [requirements]. They can lend out the deposits they have, and if they have an opportunity to make more loans — either mortgage loans under non-leverage rules — or to actually back construction or new means of production — then the Treasury will provide them with the deposits to lend out.

In effect the Treasury would be doing what it’s supposed to be doing under Yellen, but not in her perverted way. It will be extending credit for banks to make productive loans, not unproductive loans.

That was the Chicago Plan, ironically developed by the University of Chicago in the 1930s.

And the commercial banks would act essentially as they were supposed to in the textbooks, deciding what kind of loans help the economy, what kind of loans are productive, and most of all, what kind of loans can the debtor — [and the economy] — afford to pay back without slowing the economy and bringing on a depression that prevents the loans from being paid.

RADHIKA DESAI: This is exactly the sort of “return to Plainville” in our banking that the financial system, as it is today, will never stand for because they have become used to essentially being allowed to create as much credit as they want in order to engage in leveraged speculation.

Borrow money to throw into speculation so that you can make much more money on the same margins.

So this is going to also be resisted, but nevertheless you can see the seriousness of the crisis by the radicalism of the proposals being made, even by quite mainstream writers.

So people have said, according to the Chicago Plan, that there should be a separation of the issuance of money from the issuance of credit.

Central banks essentially would issue central bank digital currencies, so that would mean that all of us would have money issued by the central bank and we would have accounts with the central bank, and then whatever private financial banks remain — I mean in a certain sense [in this scenario] there need be no private financial sector — [they] could only lend against extremely high reserves, which would reduce their profitability.

So this would again transform the financial sector into a public utility and not the casino that it currently is.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well that’s really the key. Who is going to create money: the government or the banks?

The banks have shown that their bank credit has not ended up in a functional way. It’s become “de-functional”.

And the losses for the US and the European banking systems already are in the trillions of dollars, and that’s even before the bad gambles on derivatives are taken into account, and we don’t even know how much that would be.

So if the Treasury does not take over the banking system deposit liabilities, then this whole week’s banking crisis is economy-wide, and it is permanent — it cannot be fixed because of the mathematics of compound interest.

Any interest rate doubles [the amount owed] in time, and as long as the interest rates rise again, you’re going to have debts double and redouble and redouble, and the economy — it will not keep pace — the economy will be shrinking and shrinking, and you’ll have an even bigger pyramid of credit and debt (two sides of the same thing) on a smaller and smaller industrial base.

RADHIKA DESAI: This is indeed, Michael, the logic of the system. We totally agree on that.

However, there are as I say deep contradictions in this, because what we are looking at is a financial system which is presided over by authorities who can be relied on — if their past behavior is any indication — they can be relied on to fight tooth and nail to keep the system private, even as crisis after crisis the financial system’s public character becomes manifest.

And they will keep it not only private, but private and the most minimally regulated.

So what we are going to witness are further strenuous efforts to keep interest rates low, to continue bailing out banks — not necessarily with taxpayers’ money — this may not be possible anymore, although they will try — but certainly with Federal Reserve-created money, which again will not be put to the use of the productive economy to create broad-based prosperity, but to keep the wealth of the rich secure.

They will continue to surrender to financial sector demands, not to be regulated on the one hand, and while on the other hand to be bailed out from the consequences of the unregulated and deregulated activities.

And there will be in the process of all a continuous flow of rhetoric about the need for freedom and how the private sector only is innovative and so on.

So this is the pattern of how the rubble will now bounce further. Because we have had lots of rubble before and (crosstalk) there it is.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well the International Monetary Fund reports that this condition already is the case with many of the Global South debts.

Now that the dollar has risen above their currencies, and their trade deficits and energy and food are exploding as a result of the US sanctions against Russia — you’re having the same system within the US economy.

Although I think you can recognize it more clearly with Argentina and Latin America and other countries.

Within the US economy, the Federal Reserve cannot escape from Obama’s zero interest rate policy without creating such large losses for the banking system’s reserves and assets and loan values that the entire system is insolvent.

You’ve already seen the little bit that the Fed has raised interest rates — you’ve seen what it did to Silicon Valley Bank and the entire banking system — which is why it was downgraded. It’s a quandary that cannot be solved without a transformation of the whole structure of banking, and that requires how people think about money and credit, which we’re talking about now.

RADHIKA DESAI: You put — as lots of people do — you put Credit Suisse and Silicon Valley Bank in the same box, and I do feel that in one way they belong in the same box, but it’s also very interesting — someday Michael, in another program, to look at the historical differences between the US and British banking systems, on the one hand, and the Continental [European] banking systems on the other.

Differences which persist to this day and which are interesting today because I think the cookie will crumble in a different way across the Atlantic. I think they will have problems, but I think that — anyway, it’ll be interesting to see what happens with Credit Suisse, with Deutsche Bank, etc.

But I also wanted to point out that I think a lot of people say they attribute the current crisis to the lowering of interest rates in the pandemic, which is what you see just here after 2020:

But in fact I would say that the US financial system entered the era of low interest rates as early as 2000, except in the middle of the decade Greenspan was forced to raise interest rates because of the downward pressure that was created on the dollar — particularly with rising commodity prices.

And of course, it only had to reach about 5% before it triggered the 2008 financial crisis, and then of course we saw them come right down to zero, and then going up slightly in the recent past and then once again having to be brought down with the pandemic and going up.

So really, for most of the 2020s, as you see, we have had a historically low level of interest rates.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well you had the dot-com bubble just before 2000, and that led Greenspan to lower the interest rate. That was temporary.

The real quantitative easing took place [when] the Obama depression began.

Ever since Obama bailed out the banks and not the economy — ever since he didn’t write down the debts to what can be paid —ever since he refused to let the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation take over Citibank and refused to declare that the largest banks — Wells Fargo, Chase — all these banks were insolvent — that refusal led to the whole debt overhead — what they called the “jobless recovery”.

They still pretended it was a recovery, but instead of calling it a “jobless depression” — which is what a depression is — they called it a jobless recovery. So it’s like “the depression recovery”.

That was a deliberate policy choice of Obama and his Treasury Secretary Geithner. That remains the policy of the Democratic Party today with some Republican support.

Their policy is to put the financial sector first, and the job of the entire economy is to reduce its living standards, cut back its corporate investment, cut back any spending except the flow of money into the financial sector.

That sounds radical but that’s exactly what’s been happening by the banks, and it’s the inherent tendency — it’s the mathematics of interest-bearing debt and finance themselves.

RADHIKA DESAI: No, absolutely. I should just clarify the reason why I still think that the low interest rate policy in the early 2000s is continuous with what we have seen since, is that, you see, back then, Greenspan lowered interest rates — in the first instance, yes, in response to the dot-com crash.

But then they kept it going because they realized that the only motor in the US economy that was chugging along at any rate was the already-brewing real estate bubble.

And in order to keep that going — because that was the only thing that was really working in the US economy because it was inflating asset values and so on — so that is the main reason.

But beyond that I agree. I mean definitely these policies have taken on a new scale and intensity since 2008.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well something happened way beyond interest rates. The collapse of 2008 wasn’t simply a product of lowering interest rates — it was fraud.

There were eight million defaulting mortgage victims that were thrown out of their houses.

The houses of eight million American families were bought out by private capital companies and turned from owner-occupied housing into rental housing. The shape of the economy changed.

This is much more than lower interest rates. It was a transformation of the American economy from a homeowner’s economy to a rental economy — from an industrial economy to a financial economy.

The Obama administration ended permanently any hopes for an American industrial takeoff until such time as his acts can be undone and you wipe out the debt overhead that is the same thing as the savings overhead of the banks in the financial sector.

As long as America bails out the financial sector, it’s bailing out the wealth of the 1%, maybe the 10%. But the wealth of the 10% is made by indebting the 90%.

If you indebt the 90% there’s not going to be any internal market to buy what labor produces, and you’re going to have the kind of unemployment that the Federal Reserve says it’s its policy to restore normalcy — with normalcy meaning: all the wealth ends up in the financial sector and we’re back into something that looks very much like neo-feudalism.

RADHIKA DESAI: No, exactly. And by the way Michael again let me agree with you first of all that Obama was doing this even though everybody and the dog was talking about the need to have a fiscal stimulus which meant a bigger government role in making the economy more productive, investing, etc.

So there’s no doubt.

Although I should also say that the voices that have been talking about that also go back to the 1980s. I mean, remember Ross Perot and him saying that if the United States wants to have an economy as competitive as Japan’s, it’s going to need industrial policy, and that implies a very different financial system.

And so yes, of course, with Obama continuing these sorts of instincts of the US ruling class, essentially you have financial markets prospering against the background of an ailing economy — something that we saw taking an extremely grotesque form, particularly during the pandemic when the economy had crashed and nevertheless financial markets — particularly after the Federal Reserve’s massive stimulus — were simply scaling ever new heights.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well Obama did something much worse. The Federal Reserve in 2009 started the practice of actually paying interest on bank reserves held at the Fed.

So a bank could borrow from the Fed at a low rate of interest, redeposit the money at the Fed and actually make an arbitrage gain.

This is, again, a transformation in the structure. It’s not just a lower interest rate — it’s not just that. It’s lowering interest rates in a way that gives banks a way to make free money by borrowing cheap from the government and lending back to the government.

This was a gigantic $9 trillion subsidy to the banks at the same time that the Democrats said, “We cannot afford to forgive student debt. We can afford to forgive the debts of the 1%. We can afford to forgive the debts of the banks that have gone under. But not the students, not the homeowners that couldn’t pay, not the victims of junk mortgage loans.”

This is the choice that both the Democrats and the Republicans are following, and that is what makes a recovery impossible for the United States without a change in policy. I don’t see how it can occur without a revolution.

The banks made no attempt to attract deposits — they didn’t have to with the Federal Reserve just funding them. Much more than just an interest rate policy.

RADHIKA DESAI: Although I should say that the practice of the Federal Reserve paying banks interest on their deposit — which previously they had to deposit as part of the regulatory structure — this practice actually began with the 2006 Financial Services Regulatory Relief Act.

And this only goes to show that I think that the practices we’re talking about are not post-2008. They go back much earlier — indeed they go back to before 2008, before 2000, and even back to the deregulatory trend that set in already by the late 1970s.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well you could say it goes back to the founding of the Federal Reserve. That was the fatal detour that the American economy took.

If you read the government reports of the National Monetary Commission at the time, the purpose of the Federal Reserve was to take monetary power out of Washington and put it in the financial centers in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston.

And the Treasury was not even allowed as a board member on the Federal Reserve. The idea was to privatize finance and essentially replace the Treasury with the private banking system.

One result was the stock market crash of 1929. And then finally the moratoriums of 1931 that you had. Then finally Roosevelt trying to fix it up.

And ever since Roosevelt the fight has been led by the Democratic party to undo everything the reforms that he tried to do, and we’re now really back to the raw banking and raw privatizations that you had already under Wilson in 1914.

RADHIKA DESAI: I think we’d have to do a whole program on the Federal Reserve.

But I would simply say, I think that the United States was certainly overdue for creating a central bank. The problem was that they created the particular type of central bank that they did — privately owned and designed in certain ways and so on. And that I totally agree with.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, so right now what do we have? We have an economy slowed down. The function of the central bank today isn’t to provide money to the economy, it’s to provide money for the banks to make money financially at the economy’s expense.

RADHIKA DESAI: Absolutely, I agree with that. And it’s also important to understand that what is not invested is consumed.

And a lot of people were getting into debt just to make ends meet — to buy the homes and the cars they needed — not for speculation.

I think it’s important to understand that the consumption part is there for two systematic reasons.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, what’s not invested isn’t necessarily at the expense of consumption. What’s not invested is paid out as interest and financial charges to the financial sector.

You don’t have industrial capital investment in means of production and factories and machinery and research and development. You have borrowing to make money financially.

So that the Fed’s mandate in practice is the reverse of helping ensure full employment.

The mandate of the Fed is to make sure that there’s enough unemployment that wages cannot rise, so that all the growth in economic surplus will accrue to the 1%, the 10%, that controls the Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate (FIRE) sector.

The whole idea after the pandemic was, there was a thought that there would be a recovery, and the idea was — the Federal Reserve said, “We don’t want the economy to recover if wages are going to go up. We want the recovery to be a jobless recovery” — like the Obama recovery was.

“We want to make sure that any recovery is in corporate profits, in stock prices, in bond prices, and real estate prices, not in living standards.”

RADHIKA DESAI: Absolutely, Michael. And I think that what becomes really clear is that there’s no doubt that the Federal Reserve is out to “cool down” the labor market — that is to say, to ensure that there is sufficient unemployment that labor does not become particularly strong, either economically or politically.

However, those who are making this argument tend to say that, therefore, raising interest rates is the wrong thing to do because inflation is episodic, it’s because of food and energy prices and the sanctions and the war, and so on, and rising monopoly power.

Both of which are true. I’m not at all saying that these are not important factors in inflation.

I would say that inflation also has one other core component. So you can see [on the bar graph], the “All items”, the “Food” component, the “Energy” component, and then [the green bar] “All items less food and energy”.

And you can see that that green bar at the end is also quite solid. This is for February 2023 figures here.

This is for core inflation, and core inflation has remained high. And I would say that this core inflation arises from precisely those fundamental productive weaknesses of the US economy which have built up over decades.

Which we have been talking about, Michael, throughout this episode and many others. Particularly (crosstalk) multiple decades, and this is not budging.

MICHAEL HUDSON: I think it’s more financialized. Much of that inflation, the largest element is the 20% rise in housing costs. That’s the financial consequence — banks are raising the price of housing and shifting into a rentier economy.

The rise in energy prices, which is the largest element in the bar chart, is a result of the American sanctions against Russia.

And as Biden said, “We have the sanctions against Russia and blocking its energy and its food and grain because this is a 10 to 20 year fight to prevent any government from playing an active role in the economy.”

“China is a mixed economy — private and public. Any country that retains a strong government power instead of letting the economy be run by the financial sector is by definition an autocracy, limiting the freedom of the banks to take over.”

“That’s why we’re fighting China and why we’re fighting Russia as the defender of China.”

And you just talked about raising the interest rates. People have been criticizing Silicon Valley Bank, saying, “Well, why couldn’t they simply hedge against interest rates?”

Well, if you have the head of the Federal Reserve Mr. Powell, saying, “We’re going to raise interest rates up to 4% from the 0.2% that they were at” — that means that every government security, every mortgage, every bond and stock is going to go down in price.

Who on Earth would be at the other side of the hedge? Who on Earth would say, “Well we promise to pay you in five years — to buy this government bond 100 cents on the dollar even though the Fed says it is only going to be worth 70 cents on the dollar” ?

Nobody would write a hedge. The hedge would have cost $9 trillion for the economy as a whole because that was how much was paid.

So if Janet Yellen now says, “Well the Treasury will make good all of the bank’s losses that have been a result of raising interest rates from Obama’s zero interest rates” — then there’ll have to be another $9 trillion.

Well with $9 trillion you can forget Social Security, forget Medicare, forget social spending — you’ll only have a government doing military spending and paying money to the banks. And the military spending is going to prevent any other country from trying to take over its [own] banking system in the way that China has done.

RADHIKA DESAI: The Silicon Valley Bank as you say, they couldn’t have easily hedged themselves against the problems that they found themselves in.

But there is also the fact that they probably blithely assumed that they would be bailed out. This was what they were trying to achieve all along.

I should also say one other thing.

Earlier you were referring to the fact that the Federal Reserve has this dual mandate. And of course you are quite right. Not only are you right that it never really respects its mandate to keep employment levels high, it is only concerned about its mandate to keep inflation levels low.

This second mandate, of keeping employment levels high, was actually written into the legislation in 1977. But as you know, within less than a year or two of the legislation passing, Paul Volcker, by imposing his interest rate shock, violated that employment mandate right royally.

So you know that the Federal Reserve only uses it to justify policies whose real purpose is to be soft towards the financial sector.

These policies are then justified in the name of keeping employment levels high.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well I don’t think that the Silicon Valley Bank actually expected to have to be bailed out.

What it expected was that deposits would continue to grow and somehow the financial system would work and it would just hold the Treasury bonds yielding a very low rate and it could afford to do that as long as it was making a lot of money elsewhere in the economy.

But it never expected depositors to actually withdraw the money. The idea was that the deposits would grow forever.

But once the banks got so selfish, so greedy, that even though anybody could make 4% by lending to the Treasury, [SVB] thought, “Well people are very lazy, they’re slow. They’re willing to leave their money here at 0.2% and let us make all the money by paying them %0.2 and ending up earning 4% ourselves.”

“We’ll make enough money so it doesn’t matter that we’re losing money on our Treasury securities. The public doesn’t have enough sophistication to know that it has a choice.”

And once people began to realize they had a choice, the whole system fell apart. That it didn’t have to be this way. And that is what is terrifying the Federal Reserve and the Treasury now — that it doesn’t have to be this way, and that if there’s a choice we don’t have to let a predatory banking system shape the economy.

The [banks] can make the money creation system work for the economy instead of vice versa.

RADHIKA DESAI: Well as you know, every time there’s a big disaster the question always arises: Are the people [who are] responsible fools or knaves?

Michael you are saying that they are fools, I’m saying they are knaves, but who knows. The situation might actually be both.

But this also actually raises a really interesting question in my mind. As I’ve been following the story of Silicon Valley Bank, I read that the initial alarm about the deposits not being safe was spread by a relatively small number of depositors including Peter Thiel, who is the Silicon Valley investor.

And perhaps in the future we will discover why they did so. Maybe they did it because they thought, “Okay let’s accelerate this process and make sure that the Federal Reserve comes in and insures our deposits — [that is, bails us out].”

So who knows, it will be interesting to find out.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well I think they were worried about an element of the [Dodd-Frank act] about bail-ins, saying that if banks couldn’t pay there was going to be a bail-in. [The] depositors over $250,000 would have their deposits cut back to make up the bank’s losses.

[That] was completely unnecessary, because if the government would have taken over the banks, exactly the same thing would have happened.

Of course they would have parceled out what was left of the banks among the various depositors.

So the depositors in Silicon Valley [Bank], because there were so few of them who were depositors at the bank — this was a very concentrated bank ownership — said, “Well we don’t want to be left holding the bag and bailed-in. Let’s jump ship right now and leave the bank a shell. After all, that’s our business model.”

“We start companies. We sell them to the public. We loot them. We leave them as a corporate shell. Let’s do the same thing to Silicon Valley Bank. That’s what we know how to do.”

Alternatives to the current banking system

RADHIKA DESAI: Michael I think we should probably wind down now. And you wanted to wind down by talking about whether we really need banking.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Yes, that’s really the question. If banking doesn’t help the economy, what is its purpose?

Certainly we need a source of credit. Every economy needs credit. But the credit is supposed to be given for something that is economically productive — to build factories, to build houses, for construction, for infrastructure — and that’s not what’s happening today.

Most credit is for financial speculation, not to finance productive capital investment, and the default rates are rising all across the board. Mortgage loans are defaulting. Auto loans are defaulting. Credit card debt is defaulting.

And nobody knows how large the losses on derivative gambles are.

So the question is: If the way that we structure banks today leads to bankruptcy of the banks and it needs [a] bailout, why not have the Treasury create public banks and simply fund the economy for public purposes?

Instead of letting the financial sector not only take over the banking system but take over the Treasury itself, and even take over the government, as you’re having under Citizens United and what’s happening today.

Are we going to have finance capitalism? Or are we going to go back to industrial capitalism evolving into socialism?

RADHIKA DESAI: I thought they had already taken over, Michael. I thought that was what we were arguing. Isn’t that so? (laughs)

Certainly I think that this is the central contradiction. And I think that the Federal Reserve’s actions will on the one hand be pulled by this reality to which Michael and I have been referring, which is the reality of the public character of banking.

Banking needs to be public.

But on the other hand — on the other side there will be another pull as well in the opposite direction, which is the desire of the regulators to pretend as though they are still running a private system which is inherently virtuous.

So Michael, and then the other thing you say, about: Wouldn’t it be cheaper and more direct for the treasury to create a national bank? Well that will be a central bank issuing what is increasingly being talked about in progressive circles — issuing a central bank digital currency, which will allow every citizen to have an account with the central bank.

You don’t actually need any other banks. In the past, you needed banks and bank branches because there was no way in which a central bank sitting in New York or Washington or wherever could reach out to the entire country.

But today with information technology that is no longer an obstacle. So I think that makes central bank digital currencies more possible.

It then evades the necessity of having these private casinos, which we call our financial system today.

And it also then can make more feasible a financial system that is oriented towards serving a productive economy that creates broad-based prosperity. So I think that we should also at some point talk about this soon.

The other thing that’s perhaps really interesting that we should kind of remember is that the United States, and most other countries, had a financial system much closer to a productive financial system in the decades after the Second World War, which is why back then you didn’t have the same rate of financial failure, and nor did you have the same levels of inequality, speculation, predation.

It’s really quite interesting what you see here [in the bank failures charts].

So this is the first chart, and what you see is from the beginning, since the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in the 1930s, you see a reduction — the regulation reduces bank failures.

And then you see these two big bars [for “1980s” and “1990s”] which show the big Savings & Loan crisis in the 1980s and 1990s. So that was a very big number of bank failures.

And then you see, again, bank failures increasing.

But the actual reality of this is revealed when you combine this chart with the next chart.

Here [in the second chart] you see the total deposits that are lost. Because what also happens in this period, particularly after the 1980s and 1990s and into the 2000s is a massive centralization of the banking sector.

So the number of deposits that were lost in these are actually the highest in the 2000s. This is the 2008 financial crisis.

And now we are seeing more bank failures and more deposits being lost.

So that you can see that the lack of — whereas in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, right through this time there were actually essentially no big bank failures to speak of.

So essentially, this is the situation. We need a more highly regulated banking system that is going to be aimed towards not only making productive investment [but also] creating the sort of economy capable of creating broad-based prosperity.

MICHAEL HUDSON: I think the point that you wanted me to make before is, we can’t restructure the banking and credit system and leave the current bailouts in place, and the current debts in place.

The enormous amount of debts that have grown as a result of the Obama bailouts — the huge $9 trillion in debts — cannot remain in the economy without [preventing the economy from developing].

This whole buildup of debt, sponsored by zero interest rate policy, has to be wiped out.

If you keep that debt, if you don’t let the banks go under, if you do not wipe out this debt, there is no way that the economy can afford to be competitive [with] other countries.

And all it will be left [with] to relate to the international economy will be military power. There’s no way that it’ll have export power, or even a financial power that is viable.

Conclusion

RADHIKA DESAI: Absolutely Michael. So that, folks, is the story of the banking system that Michael and I wanted to share with you today.

Really, the answer to this is not only — I think the progressive economists are right to point out the dangers of the anti-labor character of the interest rate increases — but while interest rate increases have to be stopped, that is not the end of it.

There has to be a root and branch reform of the financial system. Only that is going to solve the dilemma which we are in today.

Now, just a brief word about our future shows. So we are going to take a break for the next fortnight, so you’ll see our next show in about a month’s time.

The reason we’re taking a break is that I’m off to Russia for several conferences as well as something of a fact-finding trip. So when we get back, one of the programs we’re going to do is the political economy of the Ukraine conflict.

I’m hoping to be able to report a great deal from what I found in Russia, and share my impressions with Michael who I’m sure will also have lots of interesting things to say about it.

Remember we are going to do our fourth and final dedollarization show sometime.

Thanks very much to you all. Thanks to Ben Norton for hosting our show on his website. Thanks to Paul Graham, our wonderful videographer. And also to Zach who always transcribes our scripts for us.

So thank you all and until next time. Bye.

京公网安备 11010802037854号

京公网安备 11010802037854号