Commentaries

Your Present Location: Teacher_Home> Wang Wen> CommentariesWhat Does a Chinese Superpower Look Like? Nothing Like the U.S.

Source: Bloomberg Published: 2018-8-28

What struckWang Wenabout Antarctica, beyond the brutality of the December cold, was the scale of U.S. operations in such an inhospitable environment and the American flag fluttering by the sign that marks the geographic South Pole. Observing the academic mission of hundreds of U.S. scientists in a region rich in resource potential, he was determined that China must catch up.

The report Wang wrote this summer for the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University of China in Beijing, where he’s executive dean, reflects China’s growing dilemma as it muscles its way into an international system it didn’t create.

For the first time in its long history, China has a truly global vision. So, inevitably, Beijing looks to the U.S., the sole superpower, for a yardstick as to what that requires—be it a blue water navy or more research stations in Antarctica.

Chinese research team members have lunch at a dock of the Great Wall Station in Antarctica, Jan. 2017.

Yet Communist Party leaders also recoil at being seen as the next global hegemon and are reluctant to shoulder the expense that goes with it. They studiously avoid the word “superpower” and see the American version of it as ideologically unacceptable and spent.

Whether China does become a superpower and whether it could sustain the costs involved are questions that will impact the world for decades. They will shape terms of trade, a changing global order, and issues of war and peace. “We don’t know,” Wang said over dinner a few floors below his institute, when asked what Chinese great power will look like. “Anything but America.”

Yet to misquote Leon Trotsky, even if China isn’t interested in becoming a superpower, superpower may be interested in it. The U.S., too, began its journey on the world stage determined not to replicate earlier colonial empires. Today, 11 carrier groups and a network of military bases span the globe to protect its interests.

China's first home-built aircraft carrier at the port of Dalian.

China may be heading down a similar path. An aircraft carrier construction program is underway. Its first overseas military base opened last year, in Djibouti on the Horn of Africa. Spending for diplomatic service is up sharply. China’s “Made in China 2025” economic project aims to displace the U.S. as the world’s technological power, while another plan calls for dominance in Artificial Intelligence by 2030.

The country raised defense spending from $21 billion in 1990 to $228 billion last year, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, more than three times Russia’s budget. The ease with which it did so—the military’s share of overall government spending actually fell—suggests China can be any kind of power it wants.

Already there are signs a Chinese model for development could gain traction against the ideals long promoted by the U.S. and post-war institutions like the International Monetary Fund.

However, if this is a superpower in the making, it may be a fragile one.

To Paul Dibb, a former deputy secretary for intelligence in Australia’s defense department, it’s telling that Beijing spends more on internal security than defense. “China will have to choose not between guns and butter,” he said, “but between guns and elderly care.”

Wang exudes limitless confidence in China’s future. It took four days to travel from Beijing to Antarctica. On the final leg, flying low over the vast icy expanse, Wang and others sucked oxygen from masks in the plane’s decompressed cabin. He is repelled by stories of colonist-era explorers like Robert Scott, who raced to plant their flags and stake territorial claims. Yet he also admires their “fearless spirit” and willingness to sacrifice.

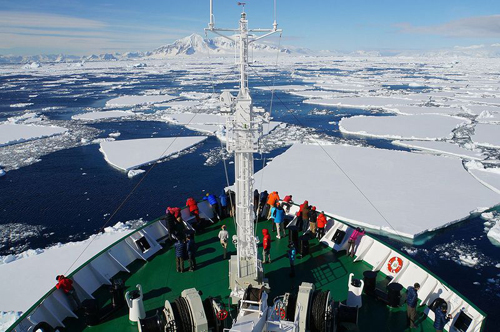

Members of a scientific exploration team from south China's Shantou University sail on a research vessel in the Antarctic waters in 2014.

“Should we contemporary Chinese be ashamed?” he wrote on his return, in the Chinese language Global Times.

An ice sheet with a mean depth of 1.6 miles (2.6 kilometers) has protected Antarctica’s resources from exploration. Still, Wang’s report says that below the surface is an estimated 500 billion tons of coal, as much as 100 billion barrels of oil, and 5 trillion cubic meters of natural gas. Despite a 1959 treaty which freezes all territorial claims, at least for now, Wang sees a “fierce” geopolitical struggle underway. He fears that, without a stronger voice and presence, China will lose out.

“President Xi Jinping has repeatedly emphasized that China must participate more actively into rule-settings in new areas, including deep sea, polar regions, outer space and the Internet,” his report concludes.

Containers used as temporary buildings for China's fifth research station on Inexpressible Island in Terra Nova Bay in the Ross Sea, Antarctica in Jan. 2018.

In practice, that would mean building infrastructure to accommodate tourists and beefing up Beijing’s research presence, the key determinant of influence in Antarctica’s multinational administration.

The U.S. budget request for the Office of Polar Programs in 2019 is $534 million. From 2001 to 2016, according to Wang’s report, China invested 310 million yuan ($45 million) in its Antarctic program. Beijing could easily afford the difference, but Antarctica is just one challenge China faces as it asserts its interests around the globe.

In January, China published its first white paper on the other pole, the Arctic, outlining its ambition for a “Polar Silk Road.” It proposes building new-design icebreaker vessels and bases, essential tools in an area with fewer barriers to territorial claims than the southern polar cap.

Silk Road is another name for the Belt and Road Initiative, into which China has already sunk hundreds of billions of dollars. Meanwhile, to match the U.S. on defense spending, China would need to find another $400 billion a year. Even for China, these are large costs.

China grasps the core lesson of the former Soviet Union’s failure—its over-reliance on military strength, according to David Shambaugh, a professor at George Washington University and author of numerous books on China. Beyond weapons, superpowers require technology, strong economies and soft power influence to sustain themselves. “China understands that,” he said.

According to Henry Wang, founder and president of the Center for China and Globalization in Beijing. True, China doesn’t want to destroy the world order that the U.S. shaped, as it has benefited from it. But it does want to create what he calls globalization 2.0, by adding new international structures including the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

“People get scared” by China’s size, according to Wang. China just wants globalization that’s more inclusive, he says.

Wang Wen is executive dean of the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University of China.

京公网安备 11010802037854号

京公网安备 11010802037854号