Commentaries

Your Present Location: Teacher_Home> Vijay Prashad> CommentariesVijay Prashad: Climate change sets workers' feet on fire: The Forty-Second Newsletter (2025)

Climate change sets workers' feet on fire: The Forty-Second Newsletter (2025)

Source: MR online

By Vijay Prashad

Update: Oct 21, 2025

Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

This summer, there were days in tropical cities when it was unbearable to walk out in the sunlight. In Mango, Togo, for instance, the temperature soared to 44°C in March and April. Heat maps depict a world on fire, red hot flames licking the planet from the equator outwards. If the air temperature is around 44°C, then the temperature of asphalt and concrete surfaces can exceed 60°C. Since second-degree burns occur in less than five seconds at 60°C, those exposed to that heat are liable to burn their skin. Walking the streets of these burning cities is hard enough with shoes—imagine what it must be like for the millions of people who lack appropriate footwear but must work outdoors during the hottest parts of the day. Only a handful of countries—most of them in the Arabian Peninsula and in Southern Europe—have bans on outdoor work to prevent heat stress. But even in these countries, it is possible to see construction workers and cleaners forced to brave the heat. This can be fatal, as was seen during the construction of stadiums in Qatar for the 2022 FIFA World Cup.

A new report from the World Meteorological Organisation and the World Health Organisation, Climate Change and Workplace Heat Stress, notes that 70% of the global workforce—2.4 billion workers—are at risk of exposure to excessive heat. The report notes that for every unit above 20°C, worker productivity declines by 2% to 3%. Workers who toil in the hot sun suffer from heatstroke, dehydration, kidney dysfunction, and neurological disorders of various kinds. Strikingly, there is no accurate number of global workplace deaths due to heat stress.

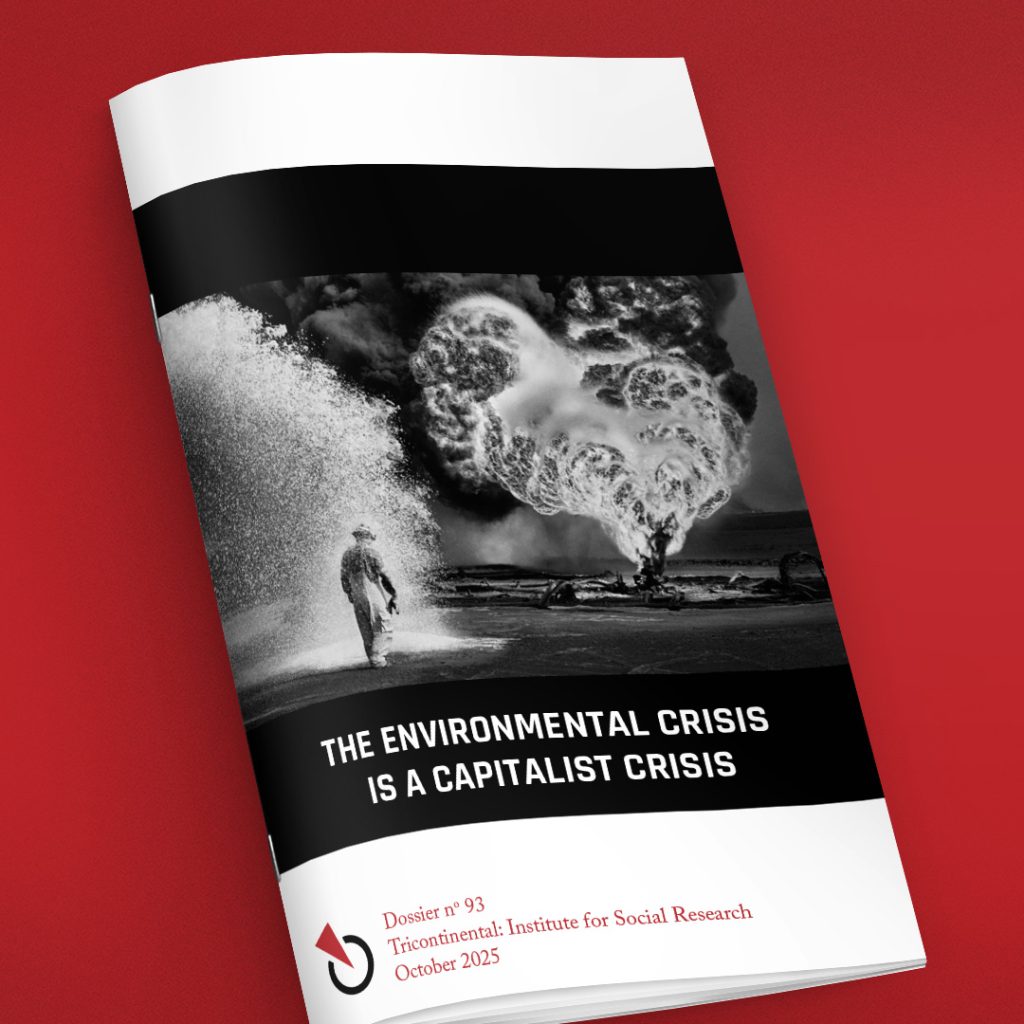

Cover of Tricontinental dossier no. 93, The Environmental Crisis Is a Capitalist Crisis. Photograph by Sebastião Salgado.

Cover of Tricontinental dossier no. 93, The Environmental Crisis Is a Capitalist Crisis. Photograph by Sebastião Salgado.

An encouraging piece of news from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is that it has created a committee to produce the Special Report on Climate Change and Cities (which will be released in March 2027). The only major study we have from the IPCC on urban centres is the sixth chapter of its 2022 report, entitled ‘Cities, Settlements, and Key Infrastructure’. Its main finding was that the one billion people who live in informal urban settlements in the Global South are in areas of great vulnerability to climate-induced disasters such as floods and droughts. Green and blue infrastructures that mitigate climate disasters—such as mangroves and wetlands—are being privatised, built over, and degraded, which further reduces the adaptive capacity of growing cities. Building on this research, the International Institute for Environment and Development has been studying summer heat waves in cities and found, in its 30 September 2025 briefing, that in forty of the world’s most populous cities the number of days in a year when the temperature exceeded 35°C has risen by 26% since 1994. Cities account for 70% of global emissions and energy consumption; we hope the IPCC report due in 2027 will consider the heat stress disproportionately borne by the international working class and spark further discussion about cities and climate change.

For now, I encourage all of you to download, read, share, and discuss our latest dossier, The Environmental Crisis Is a Capitalist Crisis. Written by our team in Brazil, this text comes in the lead up to the thirtieth United Nations Climate Change Conference, or COP 30, meeting in Belém, Brazil, next month. It will be shared and debated in pre-meetings across the world with those who are part of the battle for climate justice.

We have little faith in the COP process, since the entire apparatus seems to have been taken over by greenwashing capitalists who want to continue the old ways while masquerading as saviours. For instance:

According to Global Witness, 636 fossil fuel lobbyists were granted access to COP 27 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. This means that there were ‘twice as many fossil fuel lobbyists as delegates from the official UN constituency for indigenous peoples’.

According to Kick Out Big Polluters, 2,456 fossil fuel lobbyists attended COP 28 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, making this group larger than almost all the delegations at the meeting.

At COP 29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, there were more fossil fuel lobbyists than all the delegates from the ten countries most vulnerable to climate change.

Nonetheless, we still believe that the COP process revitalises debates that are necessary to shape and sustain the consciousness of people’s movements.

Illustration of Tricontinental dossier no. 93, The Environmental Crisis Is a Capitalist Crisis.

Illustration of Tricontinental dossier no. 93, The Environmental Crisis Is a Capitalist Crisis.

Out of the many important points in our dossier, I would like to highlight eight demands from an agenda to confront the environmental crisis generated alongside Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement (MST):

Hold the Global North accountable for ecological debt. The old colonial states have abused the carbon budget and made empty commitments to the Green Climate Fund. It is time to pay up.

End Greenwashing. Reject the idea of carbon markets and offset schemes that commodify the commons (air, biodiversity, and forests).

Advocate for community, not corporate, control over environmental policy.

Advance agrarian reform and defend the land of peasants and indigenous communities. Constitutionally mandate and implement land redistribution, collective land rights, control over seeds, and protection of biodiversity.

Build food and water sovereignty. Replace export-oriented monocultures with agroecological and cooperative food systems that democratise food production and distribution. Prioritise the right to food over the right to profit from food.

Enforce reforestation under community control. Protect the large carbon sink rainforests.

Criminalise ecocide. Build legal regimes to penalise transnational corporations that destroy nature and prosecute them both in their home countries and where they commit the crimes.

Implement a just, planned, and socialised energy transition. New energy forms should be democratically controlled and not run for financial speculation.

We are eager to debate these points in our communities across the world. These discussions should not take place behind closed doors.

To further broaden the discussion surrounding COP 30, our researcher José Seoane has produced a podcast in Spanish called Los pueblos frente a la crisis climática (Peoples Facing the Climate Crisis)—you can listen to the first of three episodes here.

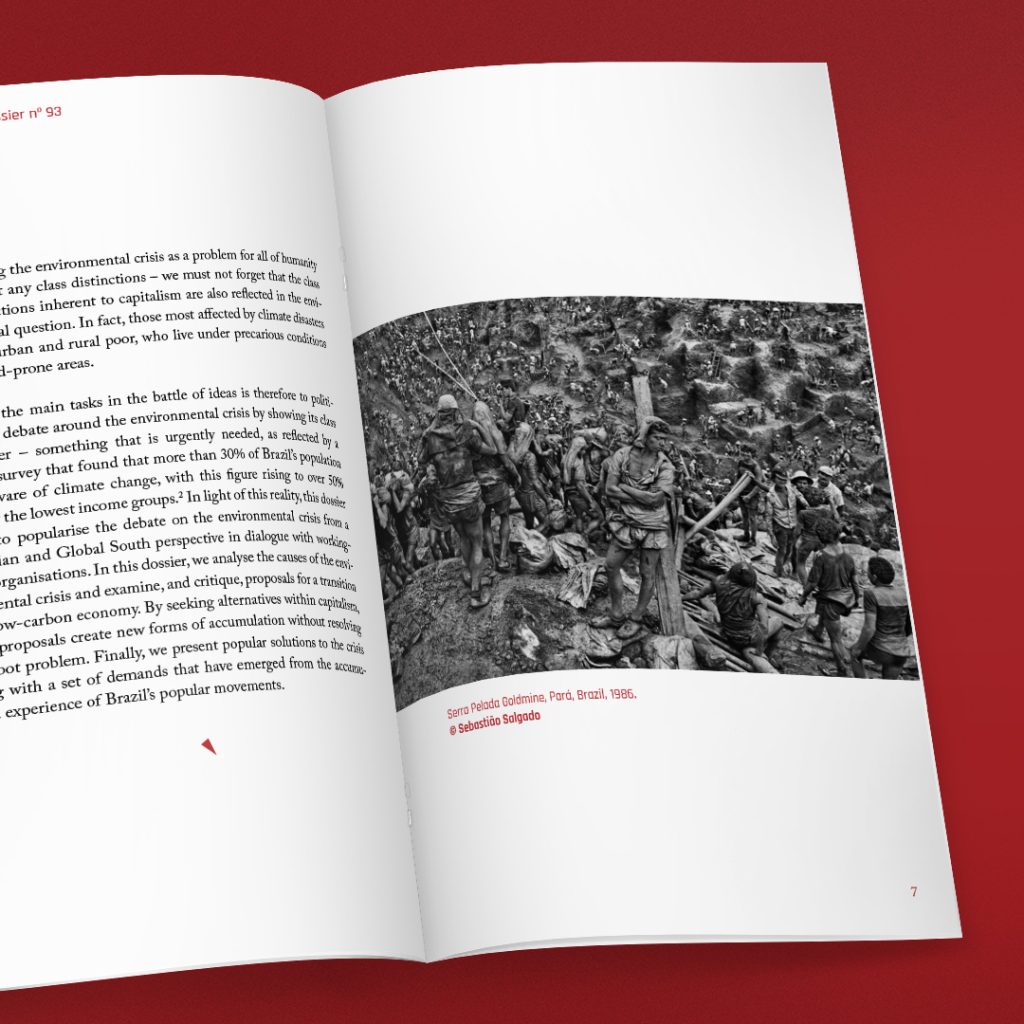

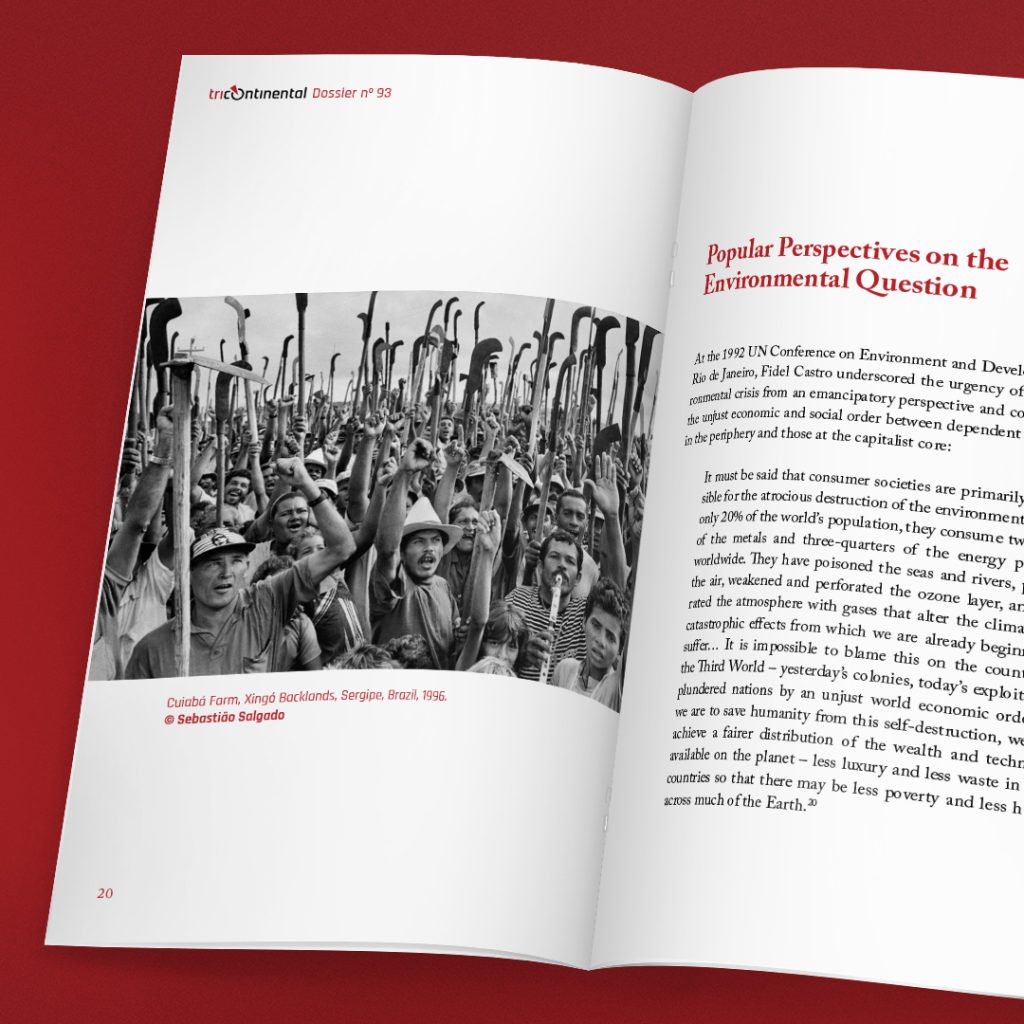

The photographs in this dossier are from the remarkable collection of Sebastião Salgado (1944—2025), a friend of the MST who established an institute for reforestation in his birthplace of Minas Gerais. It is little known that Salgado began his career as an economist with the International Coffee Organisation, an agency supported by the United Nations. It was his visits to coffee farms around the world that sparked his appreciation for the power of workers. He exchanged his pen for a 35mm Pentax.

Illustration of Tricontinental dossier no. 93, The Environmental Crisis Is a Capitalist Crisis.

Illustration of Tricontinental dossier no. 93, The Environmental Crisis Is a Capitalist Crisis.

On 13 March 2024, Julio César Centeno went to work in the orange and lemon orchards owned by Grupo Ledesma, one of Argentina’s most lucrative businesses, posting revenues of $823 million in the last twelve months. These orchards are in Jujuy province in northern Argentina in the town of Libertador General San Martín, named after a leader of South America’s wars of independence against Spain. On that day, the temperature in the fields exceeded 40°C. Centeno, also known as Penano (the Sufferer) and Brujo (the Sorcerer), began to complain of heat stress not long after his workday started at 10 am. But there was no respite. Hired by ManpowerGroup, a U.S.-based transnational provider of temporary labour, Centeno was forced to continue climbing tall ladders to harvest lemons. By noon, he suffered a seizure and fainted. It took an hour for the ambulance to arrive, after which it wended its way to the Oscar Orías Regional Hospital. The doctors tried to revive him, but he died of septic shock.

Ledesma, which has an ugly history—having disappeared dozens of workers during Argentina’s 1976—1983 dictatorship—did not pause. Unphased by Centeno’s death, the company forced the workers—who harvest 500 kgs of fruit a day—back to the orchards. The Argentine Union of Rural Workers and Stevedores (UATRE) released a solidarity statement two days later, but these contract workers do not have any real power to pressure the firm.

Centeno’s death is not unusual. There are so many stories of workers hired without legal or union protections who die of heat stress—burning alive for profit.

Warmly,

Vijay

Key Words: Climate Change, Ecology, Environment

京公网安备 11010802037854号

京公网安备 11010802037854号