Commentaries

Your Present Location: Teacher_Home> He Weiwen> CommentariesHe Weiwen: China-U.S. Decoupling Is Just a Daydream

By He Weiwen Source: China-US Focus Published: 2019-11-28

The New Economy Forum in Beijing sent a meaningful signal recently: It’s not only academic leaders but members of the public in China and the United States who are worried about the possible decoupling of the world’s two largest economies. Decoupling, in the words of Henry Paulson, former U.S. treasury secretary, would mean the rise of an “Economic Iron Curtain.”

Decoupling has been advocated repeatedly by White House hawks as a way of curbing China-U.S. relations in economy, trade, investment, technology and people-to-people exchanges. Their purpose is to check China’s rise as a strategic rival. The unilateral tariffs, the Huawei ban, strict restrictions on Chinese investment in the U.S. and the fast-growing entity list of Chinese companies that are out of favor, to name but a few examples, are the latest policy moves in this direction.

Ironically, economic developments over the past year have proved just the opposite. Tesla, Exxon-Mobil, Ford and Boeing are stepping up their investments in China. The Second China International Import Expo in Shanghai recently featured a U.S. business pavilion much larger than any other participating countries.

Craig Allen, president of the US-China Business Council shrugged off the possibility of decoupling. He said that 97 percent of respondents in a recent member survey were making money in China, and there was little evidence that they wanted to leave.

What it would cost

According to China’s Ministry of Commerce, U.S. business sales in the Chinese market reached $606.8 billion in 2016, with a profit of $39 billion. Decoupling would mean those sales and profits would be gone.

General Motors has 10 joint ventures in China. It sold 3.64 million units in the China market in 2018, 43.3 percent of its world total (8.4 million units), more than it sold in the U.S. As its European division has been sold to PSA, France, it has only two leading markets in the world — the U.S. and China. If the China market is lost, its total sales would fall to 4.76 million units worldwide. GM would then be a second-tier auto maker globally, and struggling for survival.

China accounted for 28.9 percent of Boeing’s worldwide sales in 2018. More than 10,000 Boeing aircraft use parts made in China. If China is decoupled, Boeing will not be able to complete its assemblies, and would lose 29 percent of its market. Hence, a crisis of survival would appear.

Apple had global sales of $265.6 billion in 2018, with profit of $59.53 billion, a stunning profit rate of 22.4 percent. A key reason is the assembly and sales in China of most of its mobile units, including iPhones. The Apple iPhone has around 243 million users in China and just 134 million users in the U.S. According to a Goldman Sachs study in 2018, if the iPhone assembly is de-coupled and moved back to the U.S., its cost will rise by 37 percent. In that event, Apple will no longer be the world’s most profitable mega company. A substantial sales price hike would lead many Chinese users to turn toward other brands, especially Huawei. The loss of the China market would put Apple in a crisis of survival as well.

Last year, the China market dependence of the top 10 U.S. semiconductor companies ranged from 80 percent for Skyworks Solutions, 63 percent for Qualcomm, 52 percent for Micron and 50 percent for Broadcom to 23 percent for Intel. Decoupling with China would shrink their global sales considerably, and they would be unable to squeeze out enough profit to support the huge R&D input required to sustain cutting-edge technologies. They too, will slip into severe difficulties.

Iron law of economics

Investment and other activities of U.S. multinational enterprises are driven by capital returns, not government policies. Most of them have become global companies, with their assets, production processes and sales distributed worldwide.

The World Investment Report 2019 by the UN’s trade, investment and development body, UNCTAD, ranks the world’s top 100 transnational non-finance companies in a transnational index that considers their overseas share, total assets, sales and employment in 2018. Of the top 100, 19 are American companies: Chevron, Exxon-Mobil, Apple, GE, DowDuPont, Johnson & Johnson, Amazon, Microsoft, Ford, Pfizer, IBM, Walmart, United Technologies, Intel, Procter & Gamble, Alphabet, Mondelez International, Oracle and GM. GM has the lowest TNI — 26.7 — among the 19 companies. However, it has made a huge investment in China. The TNI of Apple was 49.9, with overseas sales in 2018 hitting $167.53 billion, compared with $98.06 billion at home.

According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, over the past 20 years, the share of overseas employment by American MNEs rose from 25 percent to 33.9 percent. In 2017, their global added value was $5.3 trillion, 2 percent up from 2016. All the increase came from overseas operations, as domestically added value was virtually unchanged.

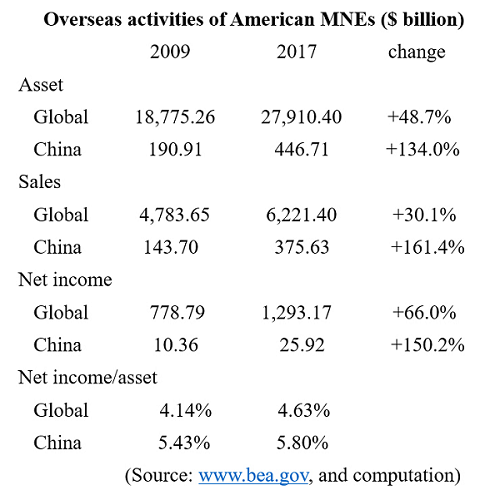

American MNEs’ China market performances has been better than their global average.

The table above shows that since the global financial crisis American MNEs have had much higher growth in assets, sales and net income in China than their overseas average, and the profitability in China was more than 1 percentage point higher. Such performance explains why U.S. MNEs will not leave China.

U.S. not in control

Data published by Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), USDOC shows that the U.S. had a high-tech trade deficit of $56.5 billion during the first half of 2019, with exports of $179.65 billion and imports of $236.15 billion, showing that it does not dominate the whole high-tech supply chain, and has a relatively high import dependence.

By sector, it had a huge surplus in the aerospace industry ($37 billion); a slight surplus in electronics, new materials and flexible manufacturing; and a huge deficit in ICT ($69.5 billion), mostly with Mexico, Malaysia and China, including Taiwan; and moderate deficits in photoelectric, life sciences, biotechnology (mostly with Ireland) and nuclear energy. Even in the aerospace industry it had a small deficit with France and Germany.

China’s high-tech imports are also diversified: Most of its imports are not from the U.S. For H1 2019, China’s ICT imports amounted to $137.6 billion. Official U.S. data show that the U.S. ICT exports to China were only $9.34 billion during this period. If the U.S. imposes a total high-tech ban on China, Europe and Japan will not follow. Huawei, for instance has already imported 1.1 trillion yen of technology and parts from Japan so far this year. Japan has replaced the U.S. as the largest Huawei supplier.

According to the Ministry of Commerce, by the end of 2018, total U.S. direct investment stock in China was $85.19 billion, 4 percent of the total FDI stock. Last year, FDI flows from the U.S. were $2.69 billion, 2 percent of the total FDI inflows into China. If there were to be a total ban of U.S. investment in China, other sources will easily take its place. In that eventuality, the U.S. MNEs will be decoupled.

A decoupling policy would undoubtedly hurt both China and the U.S. However, in the end, all the talk is just so much daydreaming. If the decoupling policy collides with the iron laws of economics, the latter will prevail.

U.S. Vice President Mike Pence was certainly right when he said that the Trump administration does not seek decoupling from China. It is earnestly hoped that he means what he says.

The author is a senior fellow of Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University of China.

京公网安备 11010802037854号

京公网安备 11010802037854号