LATEST INSIGHTS

Your Present Location: LATEST INSIGHTSFareed Zakaria: Think the trade war with China hurts now? Just wait.

Source: Washington Post Publiced: 2025-05-02

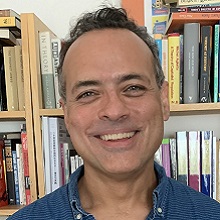

By Fareed Zakaria

Host of CNN, Political commentator

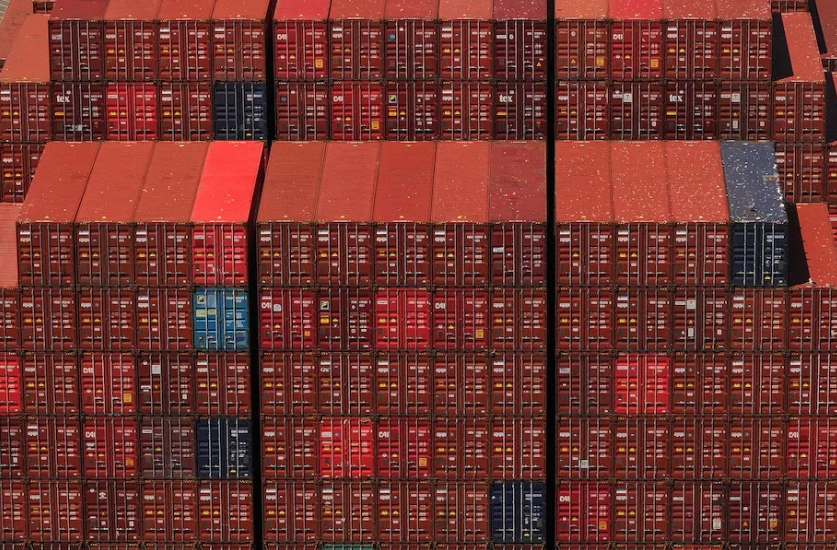

Let’s step back for a moment and recognize where we are right now. The United States has launched a trade war with the world’s second-largest economy, China. Together, the two account for almost 45 percent of global output and more than 20 percent of global trade. And it has entered this battle with remarkably little planning or forethought. Do we have a sense of where these growing tensions will lead?

It would be easy to blame the Trump administration for shooting first and thinking later. More than 80 percent of all smartphones imported by the United States come from China, as do 78 percent of all computer monitors. Can we find new suppliers for these in the next few months? Meanwhile, China imports lots of oil, gas, soybeans and pork from the U.S., which can be easily bought from other countries around the world.

The truth is, the U.S. has been sleepwalking into increased economic warfare with China for several years, probably starting around President Barack Obama’s second term. All previous measures, however, were small-bore compared with where we are now. Tariffs against most Chinese goods are at 145 percent, and China’s tariffs against most American goods are at 125 percent. As Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has said, this basically amounts to a trade embargo, which he admitted is unsustainable. (Which, of course, raises the question: Why did Bessent’s boss initiate a strategy that cannot be sustained?)

China and Xi Jinping played an important, maybe central, role in the rupturing of relations. In 2015, before Trump was elected the first time, Xi announced his major new “Made in China 2025” economic project, an ambitious set of policies explicitly designed to make China less dependent on Western technology. Xi had already aroused U.S. suspicions by making a series of foreign policy moves that were more ambitious, adventurous and militaristic than those of his predecessors. Add to this the reality that trade with China had caused job losses in America (especially in electorally important states), and the rise of more hawkish U.S. views regarding China was inevitable.But would a less-entangled relationship reduce strategic risk? First, decoupling of the two economies would make the U.S. poorer. Under one tariff scenario, Oxford Economics said U.S. gross domestic product could be 1.4 percent lower than it would be otherwise. That’s hundreds of billions of dollars of wealth lost annually. There are also second-order effects: inflation, as companies shift supply chains; productivity losses from diminished specialization; and the opportunity costs of disrupted innovation ecosystems. Trade flows will become distorted as Chinese companies set up new ventures in Southeast Asia, Mexico and other places to bypass tariffs. Smuggling will boom.Every U.S. action will produce a Chinese reaction. Consider technology. Though Washington has valid reasons to limit Beijing’s access to the highest-end chips, has doing so been effective? In chipmaking and in artificial intelligence, Chinese firms such as Huawei and DeepSeek appear to be able to produce results that are close to the cutting edge, but often at a fraction of the American cost.

Nvidia chief executive Jensen Huang this week noted that half of all AI researchers in the world are Chinese and that China is just slightly behind the U.S. in overall AI capability. He also explained, more crucially, that the country that “wins” in technology is sometimes the one that applies innovations fast and well — not the first-mover. So, have Washington’s expensive and cumbersome bans on technology only spurred China to innovate and become a fast follower, and could it end up in a better place than if these bans had never been enacted in the first place? It’s an uncomfortable question, but it must be asked.

Finally, what would a world in which the U.S. and China have little economic relationship with each other look like? Keeping the two countries deeply intertwined economically — trading, investing and interacting with each other — is a force that makes outright conflict more complicated. It is not a guarantee against war, but surely it is a disincentive.

A cautionary tale comes from the past. In 1940, as Japanese aggression in Asia grew, the United States placed an embargo on the trade of certain items with Tokyo. In July 1941, the U.S. froze Japanese assets and cut off oil exports to Tokyo in response to Japan’s invasion of Southeast Asia. At the time, Japan imported nearly 90 percent of its oil from the U.S., and the embargo left it with very limited strategic reserves.

京公网安备 11010802037854号

京公网安备 11010802037854号